#FromtheArchives: Before Title IX, rural Iowa was a 'utopia' for girls in sports

In 1970, 20% of all girls playing high school sports in the United States were from Iowa!

Hi, friends! Happy Final Four day. In just a few hours on ESPN, we’ll get to watch Virginia Tech and LSU, followed by South Carolina and Iowa, face off for a spot in the national championship game, which will be played in Dallas, Texas and aired on ABC this Sunday afternoon.

I’m going to focus in on just one of those teams today: Iowa, which is back in the Final Four for the first time in 30 years, when the legendary C. Vivian Stringer coached them to the biggest stage in the sport.

Now, this is not another Caitlin Clark Coronation piece. Rather, I want to talk about the significance the state of Iowa has to the history of girls’ and women’s basketball, and sports in general.

First of all, if you’re not familiar with the history of six-on-six basketball in Iowa, I highly recommend that you check out this playlist with excerpts from a PBS documentary on the sport. There’s also this great ESPN article about six-on-six basketball that features Iowa associate head coach Jan Jensen, whose grandmother was a six-on-six star.

Per that ESPN article and the National Endowment for the Humanities, in 1970, 20% of all girls playing high school sports in the United States were from Iowa. That is remarkable.

It also brings us to the main crux of this newsletter, which is how that statistic came to be!

We’re going to be looking at an excerpt from a three-part series on women in sports published in Sports Illustrated by Bil Gilbert and Nancy Williamson in the spring of 1972 entitled, “Women are getting a raw deal.” I broke down the first article of that series back in December, and if you missed it, I highly recommend that you take a moment to check out that newsletter right now.

In honor of Iowa’s Final Four berth, I want to hone in on the latter half of the second article, which gives examples of cities and states all over the country that are providing next-to-zero resources, at best, to girls and women in sports.

But then Gilbert and Williamson contrast this with rural Iowa, which “surprisingly enough” offers “conclusive proof of the viability and rewards of female athletic equality.”

What follows was, to me, an absolutely FASCINATING dive into how Iowa made this happen. I had heard bits and pieces of this over the years, but loved reading about it in one place.

Here are the stats from the article, with the emphasis mine:

Currently 488 Iowa high schools belong to the state athletic association for girls, which sanctions 17 championships in 13 different sports. The situation is so uncommon that it is worth calling the roll of lowa games. They are currently: basketball (438 schools participating); track (423): softball (302): golf (247); tennis (86); distance running (82); coed golf (77); volleyball (65); gymnastics (49) swimming (46): coed tennis (26); synchronized swimming (9): field hockey (6).

Coaches of the girls' teams, most of whom are men, are paid exactly the same as coaches of boys' teams; if a school can afford assistant coaches for boys' teams, it will also have assistant coaches for girls' teams. The girls' teams are fully equipped, have the same practice facilities, travel in the same style and are given the same school rewards as boys' teams. Girl athletes in lowa are not regarded as freaks. As a class they tend to be the most popular girls, enjoying more status in the eyes of other students, their teachers and townspeople.

In the smaller communities of the state where high school athletics are the principal local excitement, girls are as much a sporting attraction as boys. The press of rural Iowa treats the competitions equally. Most interscholastic basketball games are scheduled as doubleheaders one girls' game and one boys' game. The next morning the reporter from the local newspaper will lead off his account and devote the most space to whichever game was the more interesting. The stories seldom are cluttered with cute, irrelevant, patronizing passages on how the girls looked. Attention is focused instead on how they played and how the contest developed.

Remember friends, this is 1972! Gilbert and Williamson report that girls would actually move to Iowa when they were in high school specifically for athletic opportunities.

So, how in the world did Iowa become this mecca for gender equality in sports? Well, as SI put it, it wasn’t some “accident of nature, because of something that existed when lowa was liberated from the Sioux, or because some unique phenomenon sprang up like wild bluebells from the dark prairie earth.”

Get this: It took **intentional planning and effort.**

We already discussed that Iowa has a storied history of girls playing six-on-six basketball. But not everyone was on board with this pastime. At the 1925 Iowa State Teachers’ Convention, it was determined that playing competitive basketball was not a suitable pastime for girls. So, the Iowa High School Athletic Union decided it would no longer sponsor girls sports.

Well, this might have been the best thing to ever happen to girls in Iowa. Because a small group of administrative leaders broke off and became the first state to establish an independent body to oversee girls sports. For about 30 years, the organization was fledgling at best. But in 1954, Wayne Cooley left his job as assistant to the president of Grinnell College to become the chief executive officer of the lowa Girls High School Athletic Union.

Gilbert and Williamson describe Cooley as a “hard-driving, fast and forceful man” who “comes on not as a crusader for women, but as both a promoter and a shrewd and pugnacious executive.”

He had an ego, and he wanted the organization he was running to be the best.

"Before coming here," [Cooley] says, "I had no special interest in women's rights. My experience was in administration: I came to be an administrator. This was a poor-relation outfit, and I wanted to make it as successful and efficient as the organization that exists for boys' sports. I suppose in a certain sense that was my competition-the group I wanted to beat."

Cooley may not have beaten the boys' athletic executives, but he surely has played them to a tie. The two groups are now equal in affluence and influence. The Union has a plush suite of offices in downtown Des Moines and operates on an annual budget of $600,000, which comes principally from gate receipts collected at girls' state championship events. Among Cooley's more important staff members is Jack North, an ex-newspaperman who distributes weekly rankings and team and individual statistics in the fashion of the NCAA or NFL. The Union also issues a monthly newspaper, sponsors clinics and conferences for girls’ coaches and does missionary work among lowa colleges to acquaint graduating seniors with the joys and rewards of coaching girls' athletic teams.

Honestly? That’s a blueprint that I wish administrators of girls sports across the country *today* would follow. While the IGHSAU oversaw more than a dozen sports, girls’ basketball was its showpiece.

Competitively, artistically and financially, the pièce de résistance of the lowa girls' program is the state basketball championship, which is held each March in Des Moines. During this five-day tournament the Veterans Memorial Auditorium is invariably sold out, the girls attracting about 85,000 fans (often they outdraw the boys' championship, held a week later). Additionally, some five to six million other spectators see the girls' game (but not the boys') via a nine-state TV network that Cooley has helped put together.

I have zero way to fact check those numbers, but oh my god, 85,000 spectators in person for a high-school state basketball championship, and five to six million spectators watching on television. In early 1970!! Incredible.

Okay, back to the article. Again, the event didn’t attract that many people out of a sense of virtue. They came because they were entertained.

In his state tournament production, Cooley surrounds his girl athletes with cheerleaders, bands, music, flags, dignitaries, slick souvenir programs and patriotic and county-fair pageantry of all sorts. In addition to basketball games, there is an impressive ceremony in which individual and team champions in all other sports that the Union sponsors are introduced to the crowd and, of course, to the press and TV cameras.

"Basketball is our big attraction," says Cooley. "We can't expect to draw the same kind of audience for, say, a tennis or volleyball championship. So we use the basketball tournament as a showcase for the rest of our activities and the other champions."

Gilbert and Williamson then zero in on Story City, a small town 15 miles north of Ames, Iowa with a population of 2,000. They describe it as “one of those John Deere, soda and sundry, grain elevator, church steeple communities, down whose main street 76 trombonists should perpetually march.” Sure!

Anyways, the pride and joy of Story City was the Roland-Story Community High School (population: 350 students) girls’ basketball team, which won the state championship in 1972 behind two All-State players, Karen Ritland and Cathy Kammin.

"Sports are very big in a little town like this," explains Dallas Kray, the Roland- Story athletic director. "We encourage a lot of sports and we have a recreation program that goes full blast in the summer. We spend about $14,000 a year on sports in the high school. It comes out of the gate receipts. I guess the girls' basketball team, what with Kammin and Ritland, is our biggest gate attraction."

(Fun fact? According to SI, Kammin averaged 41 points a game in 1972. I read that right after Caitlin Clark’s 41-point triple double in the Elite Eight and squealed out loud. I love coincidences like that.)

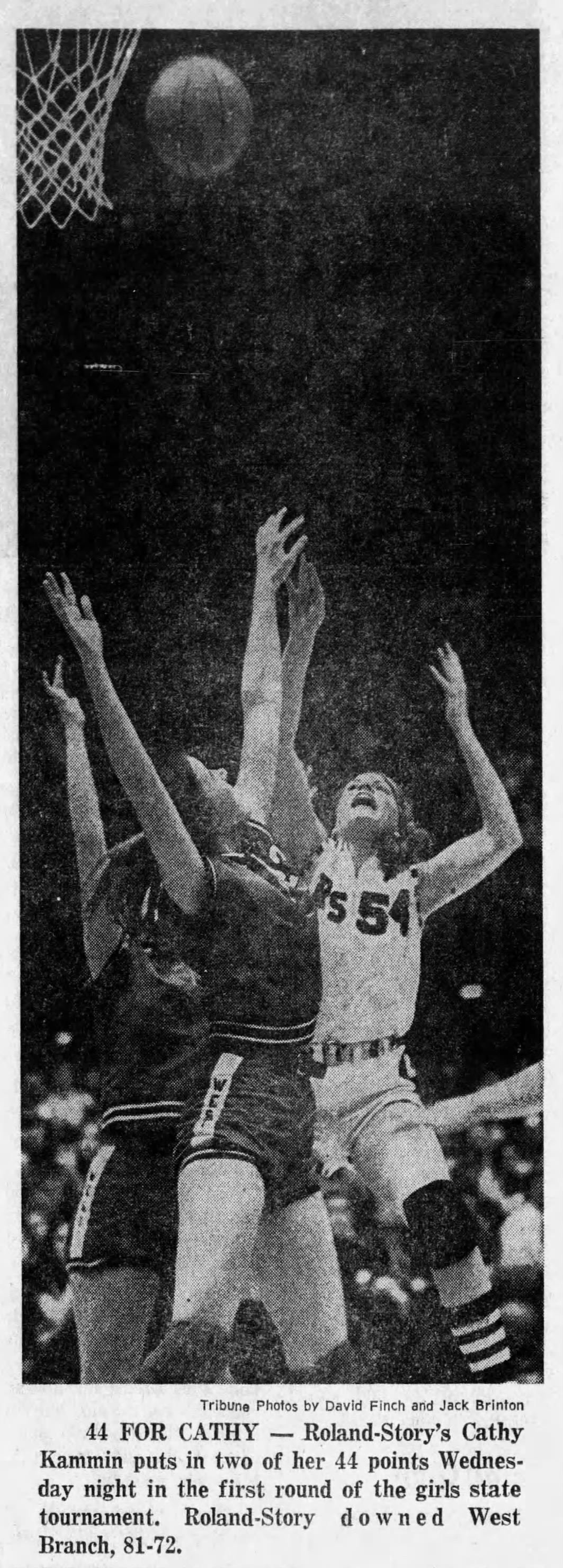

Let’s pause for a photo of Kammin in action from the Des Moines Tribune on March 9, 1972.

Okay, back to Story City, where Gilbert and Williamson want everyone to know that the boys in town are actually okay with the success of girls sports! It has not ruined their masculinity.

Sitting in the Roadside Cafe with Cathy Kammin, Karen Ritland and two members of the boys' basketball team, Alan Eggland and Jim Johnson, and talking about discrimination against girls in sports is an unusual experience. Reports have filtered into Story City about inequality between the sexes. The four teenagers find it hard to relate to these phenomena, just as a 15-year-old Ugandan might be unmoved by accounts of racial discrimination in Alabama.

(Just in case you forgot this was written in 1972 for a minute, that metaphor will snap you right back to reality.

Moving on …)

"Gee, no, I can't think of any way we're treated much different than boys," says Ritland. "We're all just basketball players."

"It's not all equal," says Johnson.

"How do you mean?"

"Well, Karen and Cathy get a lot more publicity than we do," and Johnson grins while both the girls look flustered. "But they deserve it. Right now they're playing better than we are."

To really hammer home the unity between girls and boys in sports in rural Iowa, we end the article with a scene in the gym, where the boys’ team is waiting patiently for the girls’ team to finish practice.

I’ll let Gilbert and Williamson finish things up.

On a midseason Thursday afternoon Bill Hennessy, the head basketball coach of the Roland-Story girls' team, is running his charges through a light, day-before-the-game drill. He is working with his forwards, setting up screens to give his bomber, Cathy Kammin, open shots. At the opposite end of the court, the assistant girls' coach has the freshmen and reserves. Kenneth (Pat) Eldredge, the boys' basketball coach, is sitting on the stage with some of his team, watching and waiting for a turn on the court. During a break, Hennessy comes over to talk. Eldredge (whose team also has won a state championship) and Hennessy are both slender, graying, soft-spoken men. They are old friends, having coached together for 16 years. "Pat, what about the comment you hear that if less time and attention were given to girls' basketball, the quality of boys' basketball in Iowa would improve?" Hennessy asks.

"There might be some truth in that." says Eldredge, smiling. "If we didn't share a gym, if we had more coaching for the boys, if the boys got all the attention, we might have a better team, but that is just a guess. What I do know for certain is that if we cut back on or did not have the girls' team, our sports program for humans would be a lot poorer. I wouldn't want to see that happen."

Whatever value sports have, men like Bill Hennessy and Pat Eldredge believe they are human values, beneficial to boys and girls alike. All those dire warnings of the medical, moral and financial disasters that would follow if girls were granted athletic parity are considered hogwash in Iowa. The local girls have not become cripples or Amazons: the boys have not been driven to flower arrangement or knitting. In fact, there may be no place else in the US. where sport is so healthy and enjoys such a good reputation.

Enjoy the basketball this weekend, friends.