Khelif and Lin's Olympic golds are a triumph for women's sport

It’s never been about protecting women’s sports. It’s about confining them.

The Paris Olympics were absolutely incredible, especially if you’re a fan of women’s sport.

From Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone and Katie Ledecky leaving their competitors in their wake on the way to their respective golds; to Simone Biles and Jordan Chiles bowing down to Brazilian gymnast Rebecca Andrade on the medal podium after the final of floor exercise, a fitting celebration of the first all-Black gymnastics podium in Olympic history, and one that cannot be erased from our consciousness, no matter what the record book says; to Dutch runner Sifan Hassan sprinting to the finish line of the marathon to claim a gold in an Olympic-record time, after winning bronze in the 5,000m and 10,000m races earlier in the week, becoming just the second Olympian ever to medal in all three events; to Hassan then accepting her gold medal at the closing ceremonies wearing her hijab, a statement move after France banned French women from competing in their hijabs at the Olympics; women at the 2024 games left us with a plethora of indelible images and meaningful memories that we will cherish forever.

But as powerful as those moments were, nobody’s victories in Paris held more significance than the ones by welterweight Imane Khelif and featherweight Lin Yu-Ting, the now gold-medal winning boxers who were dragged into a public debate over gender in sports and treated as props in a bitterly ugly culture war by everyone from celebrities to journalists to the president of the International Boxing Federation (IBA).

Power Plays is sponsored by the Working Family Party’s “Basketball House,” an organization that seeks “to build political power for the multiracial working class by creating community in our fandoms and making collective civic engagement convenient, accessible, and fun.”

The WFP is collecting feedback from WNBA fans about fan experience, labor environment for players, and more, ahead of the upcoming collective bargaining agreement negotiations between the WNBA Players Association and WNBA. You can fill out their survey here to have your voice heard!

Some have painted their victories as a stain on women in sport. But in reality, no wins at these Olympics are more emblematic of the journey of women in sport. By refusing to back down and performing their best under extremely trying conditions, they made the world better for women at large — even for the women who have bullied them relentlessly.

The heroines

Lin, a 28-year-old from Taiwan, started boxing as a child to help protect her mother from domestic violence. Khelif, a 25-year-old from Algeria, got into boxing at age six, and sold scrap medal to afford the bus fare to get to practice. Both competed at the Tokyo Olympics and lost early, and both continued to compete on the international stage, without incident, until the 2023 world championships, when the International Boxing Association (IBA) disqualified them due to failed eligibility tests.

There is a lot we still don’t know about what happened that week. But we do know that the IBA has not specified what tests they administered or what the results were. We know Khelif and Lin are not transgender women — they were born girls and have identified and lived and competed as such throughout their lives. We know that the IBA had no clear policy or procedure about gender testing as of March 2023.

Many assume that Khelif and Lin are athletes with disorder of sexual development (DSD), a rare genetic condition that results in higher levels of testosterone than the average cisgender woman and XY chromosomes, but we do not know if that is the case. The IBA has offered zero proof.

We know that the IBA is so corrupt and intertwined with Russian money and influence that the IOC no longer allows it to oversee Olympic boxing, meaning the organization had a major incentive to cause chaos at the Olympics. We also know Khelif and Lin met the IOC’s eligibility standards. They did nothing wrong.

And yet, as the Olympics began, there started to be murmurs about two female boxers competing in Paris who had failed gender eligibility tests.

The hysteria

The uproar hit a crescendo after Khelif’s opening match against Angela Carini of Italy. Just 46 seconds into the match, after getting hit in the face by Khelif twice, Carini withdrew from the match. Afterwards, she implied in a teary press conference that she was worried for her safety.

The incident was immediately dramatized by journalists covering the event, many of whom had only come to cover the match because of the allegations against Khelif.

“Utterly heartbreaking hearing the Italian boxer Angela Carini in the mixed zone. Blood on her shorts. Broke down in tears as she explained that she had never been hit so hard before. Added that she came her to honour her father, that she was a warrior, but had to stop,” wrote Sean Ingle, the chief sports reporter and columnist at the Guardian. Ingle then posted a selfie with Carini and said she “maybe” had a broken nose.

But those accounts didn’t line up with reality. Actual photos showed that the blood on Carini’s shorts was barely a speck. Her face in Ingle’s selfie showed zero signs of injury. And video of the fight reveals nothing excessively violent or vicious.

The day after Carini’s loss, she issued a public apology to Khelif, saying that her shun of Khelif after the match was not a sign she believed Khelif should have been banned from the competition. “I was angry, because my Games had already gone up in smoke. I have nothing against Khelif and on the contrary if I happened to meet her again I would give her a hug,” she said.

But it was far too late. As we’ve covered repeatedly in Power Plays, many powerful people have become obsessed with keeping trans women out of women’s sports under the guise of “fairness” and “protecting women’s sport.” While Khelif is not transgender, that did not matter; her defeat of Carini instantly became a rallying cry for high-profile anti-transgender advocates such as J.K. Rowling, Elon Musk, and even Donald Trump.

Their agenda was simmering long before the match took place; Carini’s tears were merely the perfect accelerant.

The headlines

It reminded me so much of what happened back in 1928, when women’s athletics were first allowed in to the Olympics. The 800m was the longest race women could participate in that year. According to sportswriters at the time, it did not go well.

“Below us on the cinder path were 11 wretched women, five of whom dropped out before the finish, while five collapsed after reaching the tape,” John Tunis of the New York Daily News wrote after the race.

“Just about every headline about the race was that it was a disaster. Women collapsing everywhere. Soon after, came calls for elimination of the event.” said Brad Stulberg. “As was the norm for the time, newspapers repeated claims of danger, injury, and permanent damage for women who dared to try to run two laps around the track.”

But those stories hardly painted an accurate picture of the race. In reality, nine women started the race and all nine finished. The winner, Lina Radke of Germany, set a world record. Some athletes sat on the side of the track after the race to catch their breath, but that’s a very normal thing seen after almost every track race, even today. So, why the tall tales and pearl clutching?

“The administrators, members of the IOC and the media apparently had decided that women were too frail to compete in a race as long as 800 meters,” said IOC executive Anita DeFrantz.

“As a result, the reports from the 1928 Games not only distorted the results of that race, but in some cases completely fabricated facts to support their viewpoint. The tragic result was that the event was removed from the Olympic program and was not reinstated until 1960.”

The hypocrisy

In the days after Carini’s cries, the spotlight on Khelif and Lin only grew. They both made it to the medal rounds with dominant but not dramatic or destructive victories.

While none of their other opponents followed in Carini’s theatrical footsteps, a few did contribute to the bullying and harassment Khelif and Lin were experiencing outside of the ring. Two of Lin’s opponents flashed double X symbols after their losses, which many saw as a reference to XX chromosomes. Her opponent in the gold-medal match, Julia Szeremeta, who recently ran for office as part of a far-right political party in Poland, referred to Lin as “him” on Instagram. Khelif’s quarterfinal opponent, Luca Hamori of Hungary shared an image on Instagram of a very petite woman fighting a giant monster ahead of her match. (In reality, Hamori and Khelif were of equal size.)

It was particularly painful to see Khelif and Lin’s opponents sow this division, because few women in sport have fought harder for inclusion than women’s boxers. And the stereotypes that have limited the sport are the exact ones their peers were perpetuating — that women are too fragile for boxing, or that boxing makes them too masculine to be proper women.

Though women’s boxing dates back to the 1700s, and was part of an exhibition event at the 1904 Olympics, it was illegal for women to box in many countries across the world until extremely recently.

USA Boxing didn’t lift its ban on women’s boxing until 1993, after a lawsuit pushed the issue. The IBA didn’t lift its ban on women’s boxing until 1994, and didn’t hold a world championships for women’s boxing until 2001. It wasn’t legal for women to box in England until 1998, when the British Boxing Council was still arguing in court that PMS made women too unstable to box. Cuba didn’t lift its ban on women’s boxing until the end of 2022.

“There were worries about whether feminine boxing could damage women’s bodies, above all when they are pregnant,” Alberto Puig de la Barca, the president of Cuba’s Boxing Federation, told Al Jazeera in 2023. (Women in Cuba still have to take periodic pregnancy tests to be allowed to compete.)

Women’s boxing didn’t make its Olympic debut until 2012. Even then, the IBA and IOC were both very concerned about how the sport would be perceived — in 2011, the IBA tried to mandate that women fight in skirts at the Olympics, so they’d be distinguishable from male boxers. (Ultimately, the choice of shorts or skirt was left up to the individual boxer.)

Given this history, it was frustrating, if not laughable, to watch both the IBA and IOC try to paint themselves as allies, or even saviors, of the sport in Paris. In the middle of the Olympics, the IBA gave a press conference so ludicrous that the Daily Mail called it “utterly shambolic.” In it, IBA president Umar Kremlev accused the IOC of “trying to do everything to destroy feminine sports competitions,” and said that because of Khelif and Lin being allowed to box in the Olympics, “female boxing is being soiled.”

IOC president Thomas Bach stressed that Khelif and Lin were victims of a “defamation campaign by a not credible organization with highly political interests,” and reiterated that the testing procedure carried out by the IBA was misleading.

“Women have the right to participate in women’s competitions. And the two are women,” Bach said.

The history

There is zero evidence that a man has ever pretended to be a woman in order to compete in women’s sports at the Olympics. And yet, there has long been a cloud of suspicion following any female athlete who displayed dominance in her sport or who had narrow hips, broad shoulders, or a muscular build.

Over the decades, officials in charge have used methods from nude parades to cheek swabs to make sure the women in competition were woman enough. (The origins of sex testing at the Olympics date back to the 1936 Nazi Games. For a deeper dive into the history, I highly recommend listening to the podcast “Tested” by Rose Eveleth, and reading the book, “The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports” by Michael Waters.)

Since 2009, when South African runner Caster Semenya broke onto the scene winning the 800m at the world championships, the subject has been in the news pretty much non-stop.

The biggest threat to women’s sports is not now nor has it ever been men on the field of play; it’s the men in the boardrooms.

In 2021, the IOC issued a policy allowing every sport’s governing body to define its own rules for transgender participation and for the participation of athletes with DSD. The announcement came with a 10-page guidance “aimed at ensuring that competition in each of these categories is fair and safe, and that athletes are not excluded solely on the basis of their transgender identity or sex variations.”

Those are great words. Unfortunately, the IOC has sat idly by over the past few years as multiple organizations, including World Rugby and World Swimming, have issued blanket bans on transgender women competing in the women’s category. It also allowed World Athletics’ policy for DSD athletes to become almost impossibly restrictive, and use questionable science to justify requiring said athletes to artificially lower their naturally-occurring levels of testosterone via medically-unnecessary means. And it allowed organizations such as the IBA to have no official gender eligibility policy in place at all.

The IOC knows, through years of trial and error, discrimination and defiance, legal challenges and loopholes, that the dividing lane between men and women is dotted, not solid. Intersex people exist. Transgender people exist. Nonbinary people exist. That almost makes it worse that they’ve been too craven to mandate policies that protect them.

The biggest threat to women’s sports is not now nor has it ever been men on the field of play; it’s the men in the boardrooms.

The hope

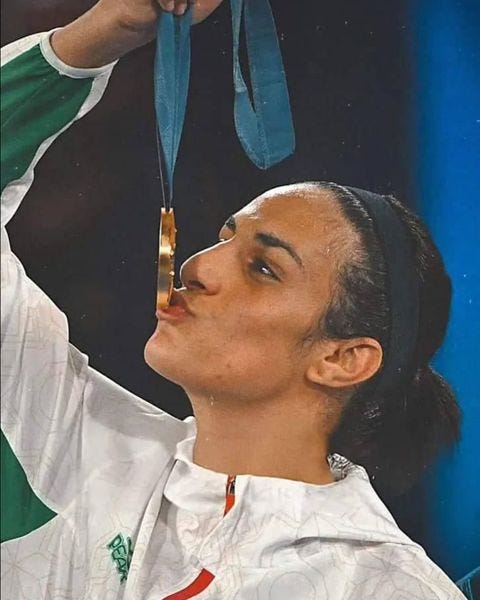

Last Friday night in Paris, Khelif defeated Yang Liu of China in a unanimous decision to capture the gold medal. When the decision was announced, Liu engulfed Khelif in a hug. On the medal podium, Khelif, Liu, and the bronze-medal winners all giggled and celebrated as a unit.

The next night, it was Lin’s turn. She beat Szeremeta in a unanimous decision, then embraced her, despite the hateful rhetoric the Pole encouraging on social media. On the medal podium, Lin even fixed Szeremeta’s hood after the medal was placed over her neck. As the Taiwanese anthem played, Lin, who had been much more stoic and media-shy during her run in Paris than Khelif, broke down in tears.

“I cried because I was so touched,” Lin said, per the Guardian. “During the fight I saw images flashing and I thought about the beginning of my career when I started boxing. There were times of great pain and joy.”

Narratively, it might have been more convenient for supporters of Lin and Khelif if they had lost early in Paris like they did in Tokyo. After all, so much of the fear-mongering surrounding athletes with DSD and trans women centers their other-worldly dominance, so it can be tempting to stress their losses as a counterpoint.

But that assumes that the arguments are happening in good faith. They’re not. How do I know? Because, once again, men are not pretending to be women in order to compete in women’s sports. Intersex women have competed in women’s sports forever. Regulations have been in place to allow transgender women to compete in women’s sport for decades. And women’s sports are stronger than they’ve ever been.

The witch hunts to weed out any scent of biological advantage end up hurting the very women that women’s sports do the most to help, the women who don’t fit neatly into boxes full of gender norms.

It’s never been about protecting women’s sports. It’s about confining them. But women’s sports are at their best when they’re pushing boundaries, not when they’re reinforcing them.

When I think back to these Olympics, I’m going to remember this video of a crowd of about 2,000 people, including the mother she fought to protect, watching her win gold at 3:30am at New Taipei City Hall. I’ll think of both women getting to be the flag bearers for their proud nations at the closing ceremonies. I’ll think of Algerians flooding the streets to welcome home Khelif, and of Khelif’s brave decision to sue Musk, Rowling, and all the powerful people who harassed her online and told lies about her gender.

I’ll think of the women who stood up to the federations that were supposed to protect them, who ignored the bullies that were out to get them, and who refused to make themselves or their talent smaller to make people more comfortable. By doing so, they made the world better for all varieties of womankind.

“The biggest threat to women’s sports is not now nor has it ever been men on the field of play; it’s the men in the boardrooms.“ I hate how true this is! Thank you, as always, for your writing.