Hello friends, and welcome to Power Plays, a no-bullshit newsletter about sexism, etc., in sports, written by me, Lindsay Gibbs.

Today’s newsletter is a long one, so let’s get right to it, shall we?

Rights in Reverse: An introduction

Today we’re starting an ongoing series entitled “Rights in Reverse,” which will examine the movement to take rights away from transgender athletes everywhere from local youth leagues to international federations.

The newsletters in this series will likely be a bit all over the place. We’ll have original reporting and highlight outside coverage. We’ll get into the weeds on policies and get to know the real people who are impacted. We’ll go into the archives to look at the history of trans participation in sports, follow anti-trans legislation across the country, and often we’ll gather here just to rant.

This is an ongoing story that deserves lenses of all shapes and sizes, but most importantly, it always needs to be told in context. I hope that this framing helps connect the dots.

But before we dive into Part 1, which focuses on University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas, I want to address the transphobic elephant in the room: Conservative politicians and activists across the world are using the concept of “saving women’s sports” to promote anti-transgender bills, and a select few prominent voices in women’s sports are furiously fanning those flames.

Because this is a women’s sports newsletter, and because I set the editorial rules here, I want to be extremely explicit about where Power Plays stands on this topic:

Transgender athletes are not a threat to women’s sports. The most pressing threats to women’s sports are, in no particular order: a lack of investment, abusive coaches, and apathetic leaders.

Transgender women do not transition so that they can dominate women’s sports. They transition because they are transgender women. Period. Rather than treating transgender athletes as an intrusion in the sports world, policies must respect their humanity and center inclusion.

At the youth level, transgender policies should be fully inclusive. Last year I did a full breakdown of a Center for American Progress report entitled, “Fair Play: The Importance of Sports Participation for Transgender Youth.” The research in that report showed that when schools have policies that discourage or ban transgender children from participating in sports, transgender students — both those who play sports and those who don’t — are more likely to drop out of school and contemplate suicide.

Here’s what I wrote at the time: “With fully-inclusive transgender policies in youth sports, yes, every now and then, a cisgender athlete will come in second place to a transgender athlete in a competition. But cisgender athletes will beat transgender athletes, too. And the cisgender athletes who win and lose and the trans athletes who win and lose will all get to experience the social, mental, physical, and emotional benefits that sports provide.

And, thanks to the inclusive policies, transgender athletes and nonathletes alike will be more likely to attend school and graduate, and less likely to be depressed and commit suicide. That, frankly, should be the end of this debate.”

Earlier this week I was about to publish this newsletter with a lengthy, caveat-filled section about holding space for “good faith” discussions about the policies for transgender participation in elite sports. But a cursory search of Lia Thomas on social media — which is not something I recommend doing, by the way — makes a “good faith” discussion feel nearly impossible, considering most of the people outraged about her victories are purposefully misgendering her.

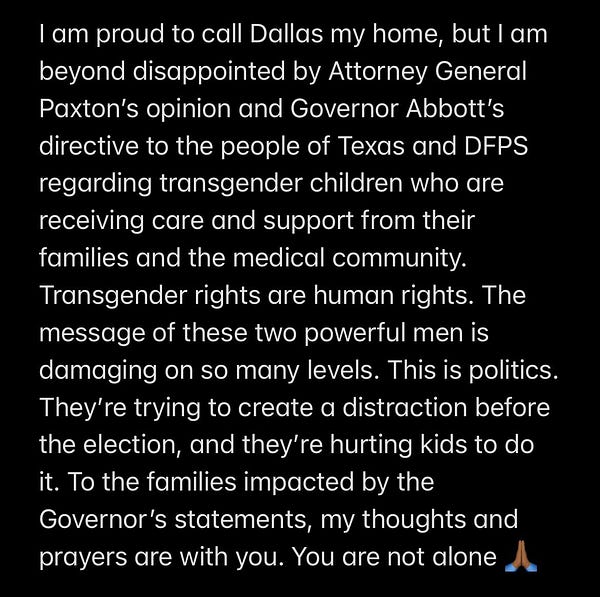

And then I saw the news that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott is calling on “licensed professionals” and “members of the general public” to report the parents of transgender youth to state authorities if they believe the minors are receiving gender-affirming medical care.

This follows Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s opinion, released Monday, stating that providing gender-affirming medical care to minors — such as puberty blockers, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgeries — is considered child abuse under Texas law.

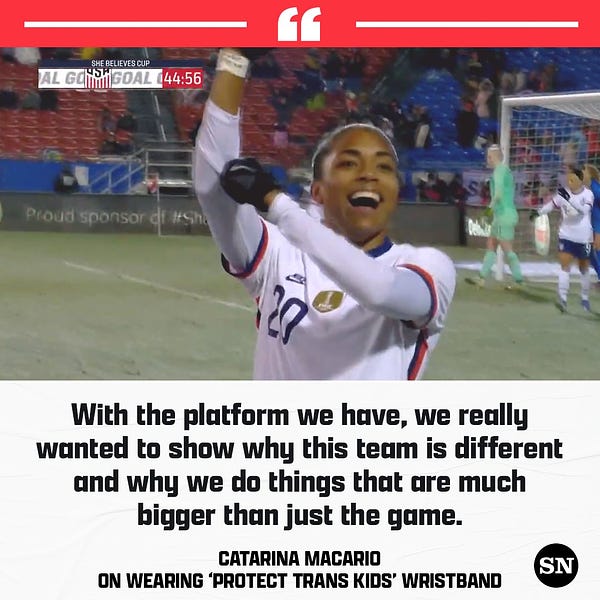

Because this is a women’s sports newsletter, I wanted to highlight that on Wednesday night, when the USWNT took the field in Texas to play Iceland in the SheBelievesCup Final, many players wore wristbands donning the message, “Protect Trans Kids.”

Dallas Wings star Arike Ogunbowale also spoke out against the directive on Twitter, saying, “Transgender rights are human rights.”

You can draw a direct line from laws banning/severely restricting transgender youth from participating in sports to Texas categorizing all gender-affirming care of minors as child abuse. And you can draw a direct line from the outrage over and demonization of transgender athletes like Lia Thomas participating in elite sports to the laws banning transgender youth from participating in sports, as Martina Navratilova discovered in 2019.

So even if “good faith” conversations around trans inclusion in elite sports are possible, I don’t actually have the space or the patience for them right now. Things are too dire. Transgender children will die because of policies being put into place right now, and no matter how adamantly the “protect women’s sports” crowd insists they aren’t transphobic, their activism is directly causing harm to some of the most vulnerable members of society.

I keep thinking about what Julie Kliegman, copy chief at Sports Illustrated, told me in an interview on the Burn It All Down podcast last week, when I asked her about the lack of urgency to the opposition of transgender sports bans sweeping the nation:

I think with sports it's a little bit tricky because everyone feels like it's kind of…I mean, not to put words in anybody's mouth specifically, but sports are seen as lowbrow or frivolous or unimportant. But that couldn't be further from the truth, because as Chris Mosier, a trans athlete and activist himself, told me, these bans are about erasing trans people from everyday life. And so they need to be taken really seriously.

Here are a few resources my friend and BIAD co-host Jessica Luther compiled to help trans kids in Texas:

This intro ended up being far longer than intended due to the current events, but I’m still going to cover the basics of the Lia Thomas story in this newsletter, because it’s important.

Okay, friends. Let’s do this.

Rights in Reverse, pt. 1: The race to stop Lia Thomas

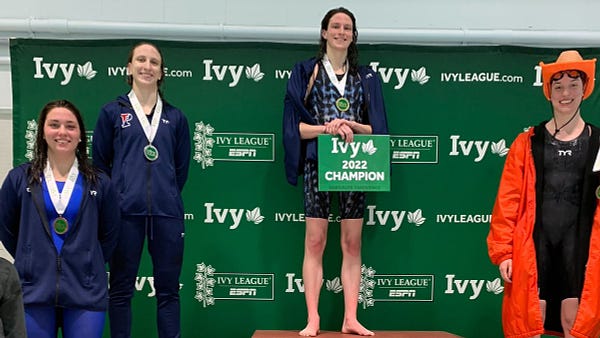

Last weekend at the Ivy League championships, University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas won the 200-yard freestyle, the 500-yard freestyle, the 100-yard freestyle, and the 400-yard freestyle relay. She was the only swimmer at the meet to win three individual events, and in the process, she captured two Ivy League records and three Blodgett Pool records.

The results generated coverage across the country, though much of it wasn’t celebratory; rather it was full of the same pearl-clutching, panic-inducing, fire-stoking rhetoric that has followed every successful Thomas swim over the past few months.

That’s because Thomas is a transgender woman, and transgender women succeeding in women’s sports are treated as a threat, not a triumph. And, at the risk of alliteration overload, that is truly a travesty.

Today we’re going to get to know Thomas and examine the frenzied efforts over the past couple of months to stop her from competing.

Who is Lia Thomas?

Lia Thomas is a very good swimmer! She swam for the University of Pennsylvania men’s team in 2018 and 2019, began medically transitioning in 2019, and in 2021, after about two and a half years of hormone replacement therapy, she began swimming on the Penn women’s team. Her times have gotten slower since undergoing hormone replacement therapy, which is to be expected.

Last December in an interview on the SwimSwam podcast — one of the few public interviews Thomas has given, and as far as I know, the most recent — she discussed her journey over the past few years.

“I first realized I was trans the summer before, in 2018,” Thomas told SwimSwam. “There was a lot of uncertainty, I didn’t know what I would be able to do, if I would be able to keep swimming. And so, I decided to swim out the 2018-2019 year as a man, without coming out, and that caused a lot of distress to me.

“I was struggling, my mental health was not very good. It was a lot of unease, basically just feeling trapped in my body. It didn’t align. I decided it was time to come out and start my transition.”

Thomas was an extremely good swimmer when she was on the men’s team. During her sophomore season, she swam runner-up finishes in the 500 free, 1000 free, and 1650 free at the 2019 Ivy League Championships.

Thomas has worked her entire life to be a successful swimmer, just like the women she is competing against. And, again I stress, Thomas did not transition so she could win swim meets; she transitioned because she is a transgender woman, and because competing on the men’s team and putting off her medical transition was negatively impacting her mental health.

She competed sparingly on the men’s team in the 2019-2020 season; she had already told her teammates that she was a transgender woman, and was in the beginning stages of her medical transition. She was eligible to compete on the Penn women’s team in the fall of 2020, but the Ivy League canceled the 2020-21 season due to the pandemic.

So she made her debut on the Penn women’s team this season. In December, Thomas set the nation’s best times in the 200 and 500 freestyle at the Zippy Invitational in Akron, Ohio, which automatically qualified her for the NCAA championships next month, March 16-19, in Atlanta.

After Thomas’s success in December, the NCAA changed its longstanding trans inclusion policy overnight

For decades, transgender participation in sports has been primarily guided by the policies of two organizations: The International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the NCAA. We’ll discuss what’s been going on at the IOC level in future newsletters. For now, let’s focus on the NCAA.

Since 2010, the NCAA has allowed transgender athletes to compete as long as they followed hormone therapy requirements, which were uniform across all sports. Athletes who were assigned male at birth and wanted to compete on the women’s team had to undergo at least one calendar year of testosterone suppression treatment before they were NCAA eligible.

Thomas, as we mentioned above, began hormone replacement therapy in 2019. By the time she debuted on the Penn women’s team she’d been undergoing treatments for two and a half years, meaning she was in full compliance with NCAA regulations.

But on January 20, the NCAA abruptly announced it had changed eligibility requirements for transgender athletes. It no longer has a uniform policy, but rather is allowing each sport’s national governing body to set its own eligibility requirements for transgender participation in their sports.

Power Plays spoke with many advocates and stakeholders who had been working with the NCAA on LGBTQ policies over the past few years; all were taken aback by the announcement.

“We did not anticipate that they would make this change so quickly, literally overnight, after they had met [with experts and LGBTQ advocates] numerous times over the past decade to talk about shifting the policy,” Anne Lieberman, the Director of Policy and Programs at Athlete Ally, told Power Plays earlier this month.

“They had a policy in place for 10 years and there was no issue, right? The only reason they changed the policy is because they don't want Lia Thomas to succeed. Point blank.”

USA Swimming followed suit with a policy surgically targeted to stop Thomas from racing at the NCAA championships

The NCAA’s new policy put USA Swimming in charge of transgender eligibility in the sport, and less than two weeks after the NCAA’s overhaul, USA Swimming announced on February 2 that it, too, had a new policy for transgender athletes in place, one that was effective immediately.

The new policy requires that transgender athletes who want to compete in women’s events have testosterone levels less than five nanomoles per liter for 36 months before they are granted eligibility.

USA Swimming also established a “decision-making panel comprised of three independent medical experts” to oversee the eligibility of transgender athletes, and puts the onus on the trans athletes to present evidence to the panel that “the prior physical development of the athlete as a male, as mitigated by any medical intervention, does not give the athlete a competitive advantage over the athlete’s cisgender female competitors.”

The policy does not go into detail about what evidence is required by trans athletes — beyond documentation of testosterone levels — or about the makeup of the decision-making panel.

While the NCAA policy change was stunning, this move by USA Swimming was downright infuriating.

Lieberman said this policy is “retaliatory” in the same way the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF)’s eligibility regulations for female classification were in 2018. The IAAF’s 2018 regulations — which, it must be noted, were based on a flawed scientific report that has since been redacted by the British Journal of Sports Medicine — were custom tailored to prevent intersex champion runner Caster Semenya from competing.

Similarly, USA Swimming’s new policy is transparently targeted at Thomas, most notably because of the specification that transgender athletes must suppress their testosterone levels for 36 months before they are granted eligibility.

According to Lieberman, the 36-month marker is “a totally new timeframe that we have never seen in sports policies focusing on eligibility criteria for trans athletes.”

It is widely known that Thomas has been undergoing hormone regulation for only about 32 months.

“It is unbelievable to me that sport governing bodies would rather restrict a talented woman's participation in sport than actually see her succeed,” Lieberman said.

“People I think really lose sight of the fact that we are talking about a young woman. She's a college athlete. She is in her early 20s. She is just trying to make it through school and swim and participate in the sport that she loves.”

Despite the policy changes, Lia Thomas *should* be able to compete at the NCAA championships next month after all

A couple of weeks ago, a subcommittee of the NCAA’s Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Medical Aspects of Sports met to review USA Swimming’s new policy, and sent a letter to the Board of Governors saying it believed it was unfair to make such drastic policy changes midseason. The Board of Governors, thankfully, agreed.

Amidst all of these brazen attempts to disqualify her, Thomas’s record-setting swims at the Ivy League Championship last weekend are all the more impressive. (ESPN’s Katie Barnes was on hand at the meet, and I highly recommend that you read their report of the atmosphere.)

I truly do not understand how she is holding herself together amidst all of the hate — which will, no doubt, only escalate leading up to the NCAA championships March 16-19.

So, I’m going to end this on a positive note, by highlighting some of the support that Thomas has received from her competitors and colleagues. A couple of weeks ago, over 300 collegiate and elite swimmers signed a letter supporting Thomas’s right to compete.

“With this letter, we express our support for Lia Thomas, and all transgender college athletes, who deserve to be able to participate in safe and welcoming athletic environments,” the letter read.

“We urge you to not allow political pressure to compromise the safety and wellbeing of college athletes everywhere.”

Additionally, as Pablo Torre and Katie Barnes pointed out on ESPN Daily, Stanford swimmer Brooke Forde — an Olympian who will likely compete against Thomas in the 500 free at the NCAAs in March — released her own statement.

“I have great respect for Lia. Social change is always a slow and difficult process, and we rarely get it correct right away. Being among the first to lead such a social change requires an enormous amount of courage and I admire Lia for her leadership that will undoubtedly benefit many trans athletes in the future.

In 2020 I, along with most swimmers, experienced what it was like to have my chance to achieve my swimming goals taken away after years of hard work. I would not wish this experience on anyone, especially Lia who has followed the rules required of her.

I believe that treating people with respect and dignity is more important than any trophy or record will ever be, which is why I will not have a problem racing against Lia at the NCAAs this year.”

Of course, as we all know, this story won’t end when Thomas’s NCAA swimming career concludes next month. Next up in this series, we’re going to dig into exactly how and why the NCAA and IOC made their recent transgender inclusion policy changes. Stay tuned.

Thank you so much for reading, especially this long one. Take care of yourselves, friends, it’s been an excruciating week on so many fronts.

This was a wonderful introduction! Thank you Lindsay for all the work you do.