The toxic culture of esports is keeping women on the sidelines

In theory, esports should be a co-ed sport. But men have ensured that's not the case.

Hello, friends, and welcome to Power Plays, a no-bullshit newsletter about sexism in sports written by me, Lindsay Gibbs.

Today’s newsletter isn’t actually written by me, though. It’s the work of freelance Power Plays contributor Benjamin Mock, who is back with a deep-dive into misogyny and harassment in esports.

So I’ll keep this brief and hand it over to them; just remember, you can subscribe to the newsletter for FREE by adding your email address to the button below. If you’d like to further support this work, membership options are available.

Where are all the women in esports?

By Benjamin Mock

Last month, the Dallas Fuel, an esports team competing in the popular Overwatch League, cut long-time player Jonathan “HarryHook” Tejedor Rua after deeply sexist comments he had made came to light on Twitter. It turns out, he frequently used derogatory slurs when talking about women.

It wasn’t necessarily a surprise that Rua made these comments; it was more surprising that he was held accountable for them. As we’ll explore in this newsletter, esports is a male-dominated, billion-dollar industry, with a deep history of misogyny — a history that the sport often fails to acknowledge.

Revisiting that history, and examining how little esports has done in the decades since to not only develop female talent, but provide a safe and welcoming community for said talent to thrive in, shows why when it comes to esports, so many women remain on the sidelines.

A brief history of gamer culture

The 1990s were a pivotal decade for video games. There was a major shift away from communal arcade gaming towards home-based consoles with the release of systems such as the SNES (1990), PlayStation (1994), and Nintendo 64 (1996); these brought with them improved graphics, more narrative-based games, and ultimately, the earliest versions of “gamers.”

The gaming community grew up concurrently with the Internet in the latter part of the decade. With increased popularity came increased scrutiny. The rise of violence-centric games such as Street Fighter (1990), Doom (1993), and Wolfenstein 3D (1994) led people to begin to discuss the impact of video game violence on their primarily young audience. That conversation reached a fever pitch after two high school seniors murdered 12 students and teachers in Columbine, Colorado on April 20, 1999. When it was discovered that one of the killers was a fan of violent video games, the media and conservative groups were whipped into an anti-video game frenzy, while gamers pushed back against being collectively labelled as mass murderers in the making.

(PIC: Alabama Senator and professional ghoul Jeff Sessions, a vocal advocate for the role video games played in the Columbine Massacre, speaks at a Senate subcommittee hearing on school safety in May 1999/C-SPAN)

This helped embed an “us vs. them” mentality in the gaming community, and that hostility towards the mainstream would only increase entering the new millennium, as games started to become more a part of mainstream culture. As gaming became more of an accepted hobby and entered mainstream culture, the diehard fans began to cloister around the idea of maintaining the purity of gaming.

“Gamer Girl” stereotypes

Of course, women became a primary target of their grievances. Two major stereotypes arose for women who dared express a love of gaming. The first was the ‘gamer girl’, a phrase first used around 2005. These were women who were perceived to only like video games in order to appear relatable. It was particularly applied to conventionally attractive women.

The other stereotype was that of the ‘gamer girlfriend’. Similar to the film trope of the ‘manic pixie dream girl’, these were women who liked video games for the “right reasons” but were also considered attractive enough to pursue romantically. They were also portrayed in direct contrast to women not interested in gaming, who men would often bemoan as being vapid and uninteresting. Their acceptance into the community was based on the condition that they were there to be dated; if they didn’t accept those conditions, they faced harassment and community exclusion.

One female gamer I spoke to on the condition of anonymity told me that she had stopped playing one of her favorite games for “a few years” after a male player had accepted her into his community in order to try and ERP (erotic role-play) with her.

As the 2000s became the 2010s, these anti-women sentiments continued to deepen, thanks to cross-pollination between gaming and communities like Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs), and the influx of women into the gaming community thanks to platforms like YouTube and Twitch..

This all culminated in 2014’s Gamergate. After the ex-boyfriend of game developer Zoë Quinn falsely accused her of sleeping with a Kotaku journalist in exchange for positive coverage of her game Depression Quest, Quinn was met by an unceasing barrage of coordinated harassment.

However, the attacks quickly spread beyond Quinn. While there were many high-profile targets, such as media critic and Feminist Frequency founder Anita Sarkeesian and game developer Brianna Wu, it was open season on any women in gaming. The proponents of this “movement” argued that what they were fighting for was better transparency and accountability in games development and journalism, leading to the now often-memed phrase “ethics in games journalism”. But in actuality, these (primarily) men, often coming from sites such as Reddit and 4Chan, saw women as tainting gaming and would do whatever it took to oust them.

Little has changed in the half-decade since then.

Esports was molded by gamer culture and now carries its torch

Esports has always been around but was often a localized thing, relegated to small cash-prize tournaments at tech conventions and local gaming stores. However, major investment from game developers, the mainstreaming of gaming, and the rise of streaming platforms have caused the scene to explode over the past decade. The Grand Final of the 2019 League of Legends World Championships, played in front of a sold-out crowd in Paris, had a peak of 44 million concurrent viewers. Meanwhile, the prize pool for the 2019 edition of DoTA 2’s The International exceeded $34 million.

The biggest allure of esports is what also makes it perfect for gender parity: accessibility. The only things you need to get into esports is a way to play your game of choice and the time to master that game.

(PIC: FPX Chinese team members and G2 European team members before the League of Legends world championships finals in 2019; via Getty Images)

However, esports’ biggest stars are overwhelmingly male and most came directly from gamer culture, bringing the culture of sexism and harassment with them.

In 2011, 121 people participated in Worlds and The International. None of them were women. Nine years later, we’re still waiting to see a woman compete at Worlds or The International, despite a steady rise in the number of players taking part — 217 competitors participated in the two events in 2019.

A woman hasn’t competed in the Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) Pro League Finals, which began in 2015, either. As for the Overwatch League — the top competition for Blizzard’s team-based shooter that has been broadcast on networks such as ESPN — 2020 marks the league’s third season. Out of 201 rostered players, only one is a woman.

While there are women working across esports — the Overwatch League’s first champions were led by GM Susie Kim, and there are women playing, coaching, commentating and broadcasting across the industry — women are still the clear minority within esports. And a big part of what’s causing this rampant gender inequality is the aforementioned gamer culture.

I conducted 14 interviews for this piece, and over half of the women I spoke with asked to remain anonymous over fears of retaliation and harassment from the esports community. Misogyny, specifically misogyny honed and heightened by gamer culture, is deeply embedded in esports.

“Right now, many teams are made up of young men who are living on their own for the first time, being coached and led by slightly older men who came up through the same ecosystem,” Cass Marshall, a former staff writer for the esports organization Immortals and a current site lead at Polygon, told Power Plays.

Talent and success don’t shield women from harassment

**CONTENT WARNING: The harassment detailed in this section might be triggering, particularly for trans readers. Please feel free to skip to the next section below.**

Every woman in esports will face harassment at one point or another, be it from fans, opponents, even teammates. But when looking at the women who have ‘made it’ in esports, there are two stories that really stand out.

Maria “Remilia” Creveling was an early star on the League of Legends scene. After bouncing around the semi-pro circuit, she joined the team ‘Renegades’ in 2015. Renegades were set to compete in the 2016 Spring Season of the NA LCS, the top League of Legends competition in North America. This made Creveling the first woman, and first transgender individual, to compete at that level in North America and made her one of the most high-profile women on the pro scene. However, three weeks into the season, she abruptly quit the team. She never found any more major success on the pro scene and devoted most of her time to streaming.

In 2018, she opened up about why she had left the LCS and Renegades. The primary reason was unbearable pain from a botched gender reassignment surgery in Thailand, which Creveling said had “left my entire pelvic area riddled with permanent numbness and intense nerve damage.” in now-deleted tweets. She also stated that Chris Badawi, Renegades team owner and a man with a dark history in esports, had promised her the surgery in exchange for her services as a player:

“Be careful of those that promise you the world. I was promised the only thing I ever wanted and I was fucked up and desperate enough to believe it,” she tweeted. “It was the one thing I wanted and I would do anything for it.”

Remilia’s Liquipedia page also cites a now-deleted press release from Renegades, who disbanded in May 2016, which attributes her departure to “anxiety and self-esteem issues”. ESPN’s article on her death in 2019 also refers to Remilia “citing pressure and harassment she received related to her appearance” as her reasons for leaving the LCS. The AP’s Jake Seiner, in his 2019 piece on women in esports, also makes reference to transphobic abuse, writing “the comment sections accompanying live streams of Renegades matches were flooded with sexist and transphobic harassment. Fans disputed her gender identity, wrote critically about her appearance and bashed her abilities."

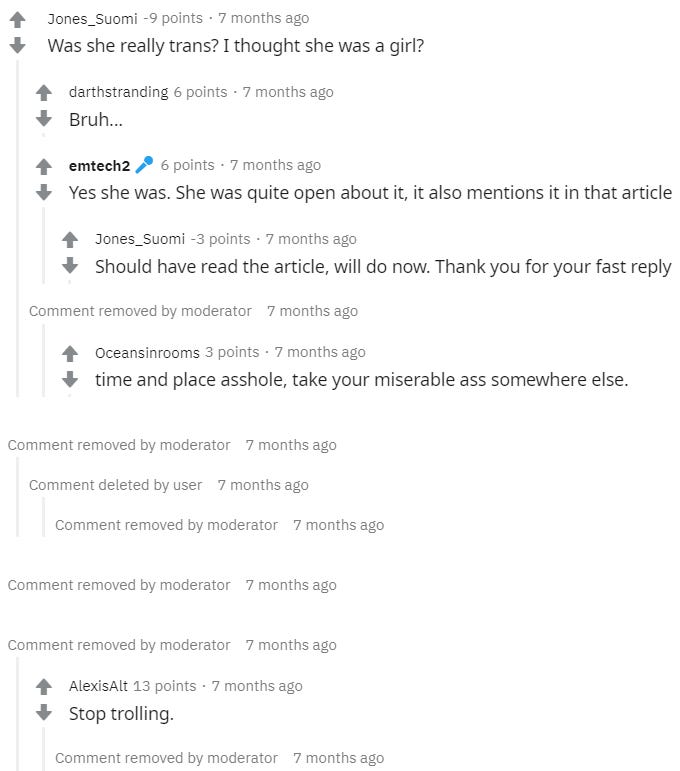

But perhaps most telling of all are the Reddit threads sharing the news of her death in December 2019, and the sheer volume of moderator-deleted comments.

If you look for news of her death on Twitter, among the transphobia you find deep mourning. One League of Legends professional calls Remilia her “role model”; many more express their devastation at the news. The news itself was broken by Creveling’s friend, esports journalist Richard Lewis. Of her death, he said "Her absence will leave a void that can never be filled."

Then there’s Se-yeon “Geguri” Kim, who first made headlines in 2016. She was 17 and making waves on the South Korean Overwatch scene with her mastery of the technically difficult character, Zarya. However, following a qualifying match for a regional tournament, two male players claimed that Kim was cheating. The accusations were echoed by the team she had beaten. According to these sources, Kim’s gameplay was too efficient and too precise. Because of this, they had concluded that she had used aim assist software to improve her performance. One of her original accusers was so confident in his assumptions, he said he would quit professional Overwatch if proven wrong.

Blizzard Korea, the regional office for the game’s developer, had Kim perform under controlled conditions at their offices. They found no evidence of cheating. Two of her accusers would proceed to quit professional Overwatch in the wake of these findings, according to Reddit user Calycae.

This incident sparked a meteoric rise for Kim. A little over a month after being vindicated by Blizzard, she would become the first woman to be signed by an Overwatch APEX team, South Korea’s top league for the game in the early days of Overwatch esports. This was followed in 2018 by her becoming the first (and to date, only) woman to be signed to a team in the Overwatch League, Two years on, she plays limited minutes off the bench for the Shanghai Dragons.

(PIC: Kim (front) at a pre-season training camp in February 2020/Shanghai Dragons via Twitter.)

Women’s-only tournaments are not the answer

With such a drastic gender gap, one would hope that the esports gatekeepers were working hard to solve it. Unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to be the case.

“I don’t see much evidence of the esports industry doing anything to address its gender problem,” said freelance journalist Jay Castello, “I can’t think of a single clear attempt to by any of the major companies in the field.”

One fan I spoke to said they couldn’t recall ever seeing a single instance of Blizzard promoting women playing in their various esports competition; the Overwatch League chose to add no women to its commentary team for the 2020 season, despite having several openings to fill. After declining to renew the contracts of the two female interviewers who had served the league for the past two seasons, this left just one front-facing woman on staff: host Soe “Soembie” Gschwind-Penski.

I reached out to Blizzard, Riot, and Valve (developers of Overwatch, League of Legends, and CS:GO respectively) about what they were doing to address the issue. I received no replies to any of my emails.

The lack of promotion or recognition for women has often led to the suggestion of more women’s-only tournaments. Women’s-only tournaments have risen in popularity in recent years. The GIRL GAMER Esports Festival has run since 2017 and features high-profile tournaments across a number of games. Other major esports tournaments, such as the Melbourne Open, now offer women’s events.

However, women’s-only tournaments are a divisive issue.

(PIC: Girl Gamer Brazil on October 5, 2019; via Getty Images)

On the one hand, these tournaments offer a form of affirmative action in a field where women are regularly denied opportunities. They are often seen as something needed in order to create a world where they are unnecessary, as Jay Castello lays out in an article for The Verge. Furthermore, as GAMER GIRL organiser Fernando Pereira noted to Castello, having these tournaments can inspire the next generation of female players. After all, you can’t be what you can’t see.

And in the very precarious world of esports, strong women’s scenes are vital for supporting the women who want to play. CS:GO has a particularly robust women’s scene, with many top teams carrying a separate women’s roster. And that’s great, it really is.

However, when you have something that lends itself so strong to mixed-gender play, having gender segregation sets an incredibly dangerous precedent surrounding the inherent skill levels of men and women. And this can be seen across forums such as Reddit, where the common argument is that there aren’t women playing at the top levels of esports because there just aren’t women with the necessary skills for that level of play. Furthermore, placing women into their own tournaments presents an opportunity for the deeply sexist community to ignore female players.

“The female tournaments aren’t exactly taken very seriously,” esports manager Kasia “Xandie” Janoszka told Power Plays.

This is particularly reflected in the prizes for women’s only events. C-Tier is the lowest classification of tournament in CS:GO. Events in this tier have fairly small prizes and typically feature small teams early in their esports journey. Last year, there was a women’s-only C-Tier event called the Women’s Esports League. Running from February to June, the prize for winning was ~$2800. This year, there was a C-Tier tournament called the OMG.BET Series. It ran during the first week of March and was not a women’s-only event. The prize for winning was $3500 (out of a prize pool of $5000).

And this doesn’t just happen at the lower levels of esports. Writing for OneZero last year, Luke Winkie highlighted the story of Emmalee “EMUHLEET” Garrido, who works full-time as a nurse because even prestigious events for women only offer a top prize of $25,000 split amongst the team. For comparison, the first year of the Overwatch League in 2018 saw players (of whom all but one were men) receive a $50,000 salary.

If women can’t make living from esports, they are less likely to pursue a career in esports.

The collegiate model has promise

While official collegiate esports is still in its infancy, and not endorsed by the NCAA, there are already signs that if nurtured, it could be a way forward for women looking to break into esports.

“I believe collegiate esports is one of the best examples of a female presence, especially from a leadership perspective…I believe it’s a more female-friendly pipeline to getting women involved in the industry (as crew, caster, or coach),” said Jennifer “FancyTuna” Frank, the former student director for varsity esports at Miami University in Ohio.

Esports are not governed by the NCAA and some colleges house their esports programs in their student activities wings or academic departments, instead of within their athletics department. Therefore, esports are not as beholden to Title IX regulations as other sports. But despite this, there are women everywhere at the collegiate level. Frank oversaw Amy Yang, an All-Star Overwatch player, and both of Frank’s predecessors at Miami were women. Many of her counterparts around the country are women. Evelynn “Evee” Le coached the University of Utah’s Overwatch team to a second-place finish at the inaugural ESPN Collegiate Esports Championship in 2019. And there are countless other women playing, coaching, and fulfilling other vital roles.

(PIC: The University of Utah Overwatch team at the 2019 Overwatch Collegiate Championships. Evelynn Le is on the far right of the front row/The Utah Daily Chronicle.)

The proportion of visible women at the collegiate level is so much greater than at the pro level. So, what does the collegiate scene have that the pro scene doesn’t?

“Students at the collegiate level are the prime audience for gender parity,” Frank said. “These are young adults that grew up alongside the grow of video games, and for a lot of them, their introduction to video games had nothing to do with gender – both men and women played Pokémon, and Spyro, and Legend of Zelda. So venturing into communities of the same age group never created a kind of gender gap – only a desire to meet others as passionate about their gameplay as they are.”

The college scene will never serve a pipeline for professional players as a player’s skills tend to peak around 18 or 19. But if it's cultivated correctly, it could become a viable place for women to hone the skills and make the connections they can use to break into the industry.

Accountability and mentorship will help improve the status quo

Esports is fundamentally a grassroots enterprise. It began with, and continues to grow through, people coming together to form teams and organize tournaments. Corporations only got involved when they saw there was a market. So, one way to enact change is to put pressure on the people at the top.

“Everyone needs to be accountable. From the big esports orgs to some of the biggest content creators, everyone needs to be held accountable,” Erin Ashley Simon, an esports broadcaster and host, told Power Plays. “Right now, it’s less about talking about it and more about acting. A continuing dialogue is crucial for change but there needs to be action that goes along with it….You got to put your money where your mouth is, you know?”

On top of holding the industry accountable, there needs to be more focus supporting women and girls who have interest in gaming early in their pursuits.

“The biggest thing I would want the industry to do is work on talent development for young women,” said Cass Marshall.

Developing talent from an early age is vital, as it is in any sport. And we’ve seen some evidence of this within esports - the NBA 2K League, which has had one female player in its three-year existence, ran a development camp for 15 women last year. Amongst the people leading the camp were two-time WNBA champion Taj McWilliams-Franklin and CS:GO star Melisa “Theia” Mundorff.

Swedish game developer and Twitch streamer Anna Brandberg set up a mentorship program for League of Legends last year, using female veterans of the game to teach women who wanted to try the game for the first time.

Kasia “Xandie” Janoszka, who manages the Overwatch Contenders team Obey Alliance, got her start in esports by reaching out to women in the industry and simply asking for advice. Now, she’s doing the same for the women who are coming behind her.

All of this is especially vital given the volatility of the esports industry. There are hundreds of esports leagues and only a handful of players will make it to the top of their chosen game. This means players and coaches regularly move from team to team for the sake of their career. Without strong mentors and connections, women are more likely to fall through the cracks.

Bringing women into esports is meaningless if esports isn’t safe for women

Whatever the industry does to help women, it will mean nothing if harassment is not treated more seriously. Women are fiercely harassed in esports and we can’t expect women to simply endure if they want to find success. Harassment needs to be treated seriously and deal with accordingly.

Right now, the way games handle harassment varies greatly but once you reach esports, it becomes abundantly clear that harassment is viewed as a lesser crime. During the inaugural 2018 Overwatch League season, Félix “xQc” Lengyel of the Dallas Fuel received a four-game suspension and $2000 fine for making homophobic comments about another player. By comparison, Chen “U4” Congshun of the Shanghai Dragons received a ~$9000 fine while Su-min “SADO” Kim of the Philadelphia Fusion began the 2018 season on a thirty-game suspension for various offences related to cheating.

HarryHook’s removal from the Dallas Fuel is evidence that change and accountability can happen in esports. But it’s not an easy road — particularly for the women who are paving the way.

A few years ago, Chinese Hearthstone player Xiaomeng “VKLiooon” Li was waiting to sign up for a major tournament when she was confronted by a male player. He told her she was in the wrong queue because “this isn’t for you”. Last November, she became the first woman to become Hearthstone Global Champion. And as she basked in her historic victory, she had a message for the crowd in Anaheim and those watching at home.

“I want to say to all the girls out there that have a dream for esports competition: If you want to do it and believe in yourself, you should just forget your gender and go for it…As long as you want to play well you can, no matter what gender you have."

Benjamin Mock is a sportswriter who is tired of women’s sport being sidelined. You can find them on Twitter.

Thank you so much for supporting Power Plays! None of this would be possible without you.