Welcome to March Misogyny

Let's dive into this current NCAA mess, and figure out how we got here in the first place.

Hi, friends, welcome back to Power Plays, a no-bullshit newsletter written by me, Lindsay Gibbs.

Today, the NCAA’s atrocious treatment of the women’s basketball tournament gets some ink, then I take a look back in the archives to see how the NCAA became the overlord of the women’s basketball tournament in the first place.

But first, a couple of announcements, because you know I can’t just jump into things, that would be far too easy:

Currently, some writers are leaving Substack (the platform that publishes this newsletter) over concerns that the company is elevating anti-trans voices. I certainly share these concerns. Here is a statement I sent to the Power Plays Slack community last week, but the cliff notes are: I am still figuring out what the future of the relationship between Power Plays and Substack will be, but due to this being an overwhelmingly busy period of life, and Power Plays being such a primary source of my income, I won’t be able to make any big business decisions in the next couple of weeks. However, I want to assure everyone that in the meantime, all the work I do on trans rights in sports (and the attacks against them) will remain in front of the paywall and free to all. Additionally, if your subscription is up for renewal or you want to finally join our legion of paid subscribers, and you don’t feel comfortable paying through the Substack platform right now, please contact me individually (lindsay@powerplays.news) and we will work something out, I promise. Thanks for your patience as I decide on my next steps.

This is an awkward pivot, but do you want to hear something cool? A Power Plays piece about how ending amateurism would help female athletes was cited in a Supreme Court briefing ahead of this summer’s big Supreme Court hearing on the NCAA and NIL. It’s really incredible to see the impact this community is having, and truly, we’re only just getting started.

Okay, Power Players. Let’s do this.

The weights on our shoulders

This is not the newsletter I’ve been diligently reporting for the past couple of weeks. This is not the newsletter I wanted to publish about the first NCAA women’s basketball tournament in two years. This is certainly not the newsletter I wanted to start out this week with.

But I make content plans, and the NCAA’s bigotry laughs.

By now I’m sure you all have an idea what I’m talking about, but for the sake of keeping a Formal Record Of Bullshit, let’s recap.

Last Thursday, the day before the men’s NCAA basketball tournament tipped off in Indianapolis, and three days before the women’s NCAA tournament tipped off in San Antonio, Stanford sports performance coach Ali Kershner took to Instagram to share comparison photos of what the men’s weight room looks like, versus the laughably small set of hand weights provided to the women.

The difference was so stark that the photo instantly went viral.

“These women want and deserve to be given the same opportunities,” Kershner wrote. “In a year defined by a fight for equality this is a chance to have a conversation and get better.”

Now, I’m going to be honest; I cover sexism in sports so often that I initially wasn’t that phased by the photo. That’s partly because I’m dead inside and have become almost numb to the onslaught of inequity in sports, but also because I assumed that even the NCAA wouldn’t be THAT obvious about how little they care about women’s sports. I figured there must be some context missing. The women’s weight room likely wasn’t as decked out as the men’s, but surely there was an actual weight room that Kershner had just missed.

But the more context I received, the WORSE the NCAA looked.

First of all, that Thursday, the main March Madness twitter account (which is for the men’s tournament only, we’ll get there in a minute), posted a full time-lapse video BRAGGING about the set-up of the men’s weight room, and the set-up was far more extensive than Kershner’s photo showed.

Then the NCAA tried to explain away the pitiful excuse for a women’s weight “room” by claiming there was limited space in the women’s facilities. But Oregon’s Sedona Prince immediately threw shade on that justification, in a brilliant TikTok that showed that the tiny rack of hand weights was surrounded by an enormous room that, besides a few socially-distanced folding chairs, had nothing but empty space.

I MEAN COME ON, NCAA!!!!!!!!

I can’t tell what I’m angrier about: The reality that the NCAA didn’t think that elite female athletes needed WEIGHTS to compete in an elite competition; the reality that absolutely nobody noticed that there was anything wrong with not giving women proper weights; or the reality that if people did notice, those in charge must have had the FUCKING AUDACITY to think that the women wouldn’t complain. Every scenario I think up is brain-breakingly more insulting than the last.

Thankfully, the athletes and coaches and trainers did speak up, and the outrage spurred action. Within 24 hours brands such as Dick’s Sporting Goods and Orange Theory Fitness stepped up to offer equipment, high-profile athletes all over the globe called out the NCAA, Sedona Prince was on CNN, and the NCAA issued apologies and constructed a weight room — proving how relatively simple it was to do in the first place.

But we all know the story doesn’t end there.

The weights are but a small part of a much bigger conversation. Alex Azzi at NBC Sports’ On Her Turf has a thorough run-down of the many disparities between the men’s and women’s tournaments — including the amount of swag in the swag bags — but I want to focus in on a few of the discrepancies that have really kept me up at night:

Chantel Jennings of The Athletic reports that the NCAA made no accommodations for mothers in the women’s “bubble,” and that even infants counted as part of each team’s 34-person travelling party.

The NCAA isn’t paying for transcriptionists or photographers at the women’s tournament until the Round of 16, while the men have both for the entire tournament. As a member of the media, I can assure you that this makes it 100 times more difficult to actively cover the women’s tournament, and honestly it feels like that’s the point.

The NCAA even treats the women as less-than when it comes to COVID-19 TESTING — women receive rapid antigen tests, while the men get the standard PCR coronavirus test. As you might guess, antigen tests are far cheaper, but also considered less accurate. And, as Dan Solomon of Texas Monthly pointed out, this is particularly egregious considering San Antonio has a lab built specifically for cheap and fast processing of PCR tests!!

And, as a fun capper, according to a Wall Street Journal report today, while the NCAA’s trademark for the term “March Madness” applies to the men’s and women’s tournaments, the NCAA made a business decision not to use the incredibly popular term — which includes a twitter account with 1.5 million followers — for the women’s tournament. I begun digging into this topic yesterday and assumed this was the case, but HOPED that there was a less obviously evil reasoning behind it. Kudos to the WSJ team for getting to the bottom of it, and for giving me another reason to rage.

On every conceivable level, the NCAA has disrespected women’s basketball, and as an extension, women’s sports as a whole and the athletes that play them. The Phoenix Mercury’s Brianna Turner summed the whole thing up perfectly:

I’m exhausted. And I know I’m not alone. I know that everyone in women’s sports, from the athletes to the coaches to the trainers to the fans are sick and tired of this shit. Being a supporter or participant in women’s sports often feels like skiing uphill with a boulder tied to your back, listening to someone who took a ski lift to the top of the mountain with a feather in their hand mock you for not beating them.

But despite all this rage and all of the weight, I’m choosing to be optimistic in this moment. In fact, I’m demanding it from myself. For the very first time in history, ESPN is airing every singe women’s NCAA tournament game on national television from beginning to end. At least six of those games are on ABC proper for the first time since 1995. This is a humongous step. And I’ll have a newsletter focused on coverage in a couple of weeks, but I’m seeing real signs that news rooms are giving the women’s tournament far more respect than they did even two years ago.

Plus, the amount of talent in the tournament is unbelievable, and the field itself is WIDE OPEN.

The NCAA might not recognize how special and important this women’s tournament is, but the players and coaches and staff and fans are going to carry it to the top of the damn mountain anyways.

#FromtheArchives: How the NCAA ended up in charge of women’s basketball

So, with all of this talk about the NCAA and women’s basketball and sexism, I’m doing something that’s probably considered taboo, and re-purposing a newsletter I put out just for paid subscribers about a year ago. (My newsletter, my rules!)

When reading Pat Summitt’s autobiography, “Sum It Up: A Thousand and Ninety-Eight Victories, a Couple of Irrelevant Losses, and a Life in Perspective,” for the Power Plays Book Club, I honed in on an era of women’s basketball that doesn’t get talked enough about, which is the decade-long reign of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW).

You see, although the NCAA was founded in 1906 and started hosting the annual men’s college basketball tournament in 1939, it didn’t host its first women’s tournament until 1982.

But because, as Pat Summitt put it, “the NCAA didn’t yet care enough about females to bother with us,” a group of passionate women administrators launched the AIAW launched in 1971 to govern women’s collegiate sports, and established the first national championship tournament for women’s basketball in 1972.

Summitt played in that first AIAW championship game back in 1972, when she was a player for UT-Martin. Here’s how she describes that experience:

It was a 500-mile road trip, but somehow, (UT-Martin athletic director Bettye Giles) and (UT-Martin volunteer coach Nadine Gearin) begged and borrowed the money to send us. After we won the state tournament in Knoxville, Bettye went to a drugstore on the main drag and bought a large glass piggy bank and literally carried it around on the street, seeking donations. For a snapshot of the women’s game in 1972, imagine a full-grown woman walking around with a piggy bank, panhandling for change.

Summitt became the head coach at the University of Tennessee in 1974, and led the Lady Volunteers to a third-place finish in the 1977 and 1979 AIAW tournaments, and a runner-up finish in 1980 and 1981.

In 1982, Tennessee opted to play in the first NCAA women’s basketball tournament, instead of in the last AIAW tournament. (The Vols made it to the Final Four.) The AIAW tried to fight the NCAA in court, but ended up folding by 1983.

So, what happened? How did the AIAW go from a savior of women’s college sports to an afterthought? Let’s visit the archives to find out. What was the AIAW’s relationship with the NCAA? And what ultimately led to the demise?

Here are three articles I came across in the archives that taught me a lot. (Though, of course, this is all just scratching the surface of a complex issue.)

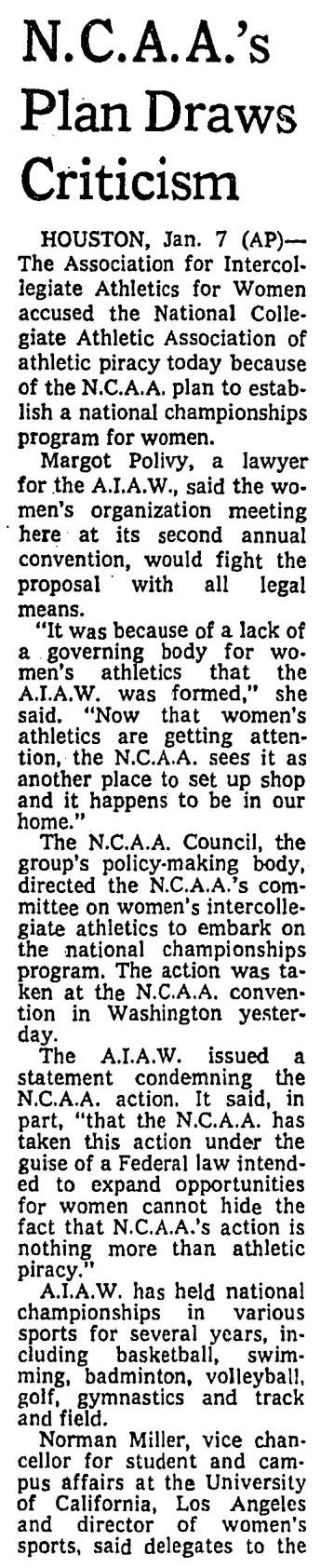

January 8, 1975, NYT: Soon after the AIAW established a base for women’s sports, the NCAA remembered that women exist

The AIAW came to life in 1971, and this article from 1975 details the AIAW’s furor when the NCAA announced, out of nowhere, that it was finally working on a plan to hold national championships for women. The AIAW accused the NCAA of “athletic piracy,” and vowed to fight the proposal.

“Now that women’s athletics are getting attention, the NCAA sees it as another place to set up shop, and it happens to be in our home,” said Margaret Polivy, a lawyer for the AIAW.

January 10, 1978, NYT: NCAA moves towards holding championships for Division II women’s sports, and the AIAW is worried, but insists it is “not an activist organization”

There’s another article I found fascinating, which shows that the NCAA, while fighting Title IX in court, kept trying to undermine the AIAW and launch women’s championships. The AIAW was constantly on the defensive, and treated like utter trash by the NCAA, but because it was the 1970s and “feminism” was still a politically-charged word, the leaders of the AIAW had to insist that they were “not an activist” organization. Such a fine line to have to walk!

May 21, 1981, The Christian Science Monitor: A deep dive into the final fight between the AIAW and the NCAA, and how the NCAA ended up winning out

The most comprehensive article I came across on all of this is a 1981 piece by Christine Terp at The Christian Science Monitor, that is, NO JOKE, entitled, “Power plays in the colleges!!!”

(This is what destiny looks like, friends.)

Anyways, I really recommend you reading the whole thing, but as it is far, far too long to post in its entirety, I’m just going to excerpt some of the most telling parts here.

Terp does a great job at establishing what is at stake right from the start, emphasis mine:

Whichever, the national championships are only the public battleground for a much larger struggle: Should women's sports be like men's sports, or should they be a whole new ball game?

While in 1975 and 1978 the NCAA’s desire to get into women’s sports had been a hypothetical, in 1981, the NCAA made the move official. It was a very controversial choice, to say the least, and this piece dives into all the pros and cons:

Last January at the NCAA annual convention, by excruciatingly close votes and slick parliamentary moves, delegates approved the championship program for next year and a plan to integrate women into the NCAA governing structure, guaranteeing them a certain number of seats on committees.

This move has been called everything from a "power play," a "blitzkrieg against a group of people who have worked hard to develop their own organization ," and "taking the women against their will" to "providing options for women's athletics" and "a fresh and renewed impetus to intercollegiate athletics for women."

The NCAA says it wants to bestow visibility, money, and the NCAA name — the name in college sports — on women. Big-time sports, just like the men.

And big-time problems, the AIAW counters. The newer women's organization maintains it offers an "alternative approach," emphasizing the rights of the athletes themselves and playing down recruiting, an approach which until now has protected women's sports from the problems that have haunted men's sports.

Each side grimly insists it's not men-vs.-women. Each side fervently declares it has the best interest of the women at heart.

The AIAW claims that the NCAA is out to take over women's sports, and control all collegiate sports. The NCAA says it simply wants to offer an option in women's sports.

The AIAW thinks the NCAA is a Johnny-come-lately, appearing just in time to reap the benefits of the AIAW's hard work. The NCAA says it's been waiting until it was sure the women were serious about athletics.

The AIAW claims it's male administrators making decisions for women without heeding their wishes. The NCAA maintains it's an Institutional decision.

The AIAW criticizes the wisdom -- and the legality -- of trying to shoehorn women into an organization designed to fit men. The NCAA says that's why the next four years will be a phase-in time, a "transitional period" during which it will examine and modify its rules to accommodate women.

So again, it came down to the NCAA only caring about women once the AIAW proved value. And naturally, this is particularly upsetting when paired with the fact that men were in charge at the NCAA, while women in charge at the AIAW:

The NCAA has talked for years about including women in its programs. It says it went ahead with this plan rather than pursue talks with the AIAW because that was the will of its members, represented, by and large, by male athletic directors. On the other hand, the AIAW membership, representing basically the same schools, showed overwhelming (282-40) opposition to the NCAA proposal at its January convention, days before the NCAA voted to adopt the plan. In this case, it was the women administrators making known their feelings about the direction they wanted their own programs to take.

And it’s important to remember that women’s sports were growing in part because of the AIAW, but also because Title IX had forced colleges to give women’s sports resources. And the NCAA, when representing just men’s sports, was so upset about Title IX that it fought the law in court for years!

The NCAA doesn't like Title IX very much. It thinks it shouldn't even apply to athletics. This is perhaps the supreme irony of the entire intercollegiate athletics brouhaha. On the one hand, the NCAA maintains it is committed to promoting women's sports. On the other, even though Title IX is widely regarded as being the key to the gym for women, the NCAA is still in court fighting it, claiming that as it is interpreted now, Title IX goes beyond what it was designed to do.

I don’t know that women’s sports would have been better off if the AIAW and NCAA had found a way to coexist, and if college sports had kept an entire organization dedicated to women’s sports, one that was primarily run by women. It’s a regular conundrum in women’s sports — and in any movement, really. Do you partner with the all-powerful leading organization, knowing that you’ll have more resources available but will often be an afterthought? Or do you stick with the people who have helped you grow from the grassroots level, knowing that success might be a much longer slog?

There’s no perfect answer, and in this case, women didn’t really have a choice thanks to the NCAA’s strangle-hold over college sports. But I think we must remember, always, how crucial the AIAW was to women’s sports, and women’s basketball in particular.

Anyways, let’s all lift some extra weights this week, both literally and metaphorically, just to piss the NCAA off.

Thanks so much for reading Power Plays, and for your continued grace and support. I hope you’re all on the road to vaccination. I get my first shot on Wednesday, and am quite excited.

I went looking for the women's schedule in the "official NCAA March Madness" app last week and was shocked to find that there was no info whatsoever. Turns out there is also a separate app oh so helpfully called either NCAA DI Women's Basketball or DI WBB that comes up when you search womens march madness on Android. It has less than half the features and honestly looks like a 3rd party app compared to the men's app. Totally ridiculous.