Equal pay at majors can't cover up unrelenting sexism in tennis

This clay season put gender inequality on the front page.

Tennis is moving the wrong direction on gender equality

Fifty years ago, Billie Jean King walked into the offices of the U.S. Open and demanded that they pay women the same amount as men. She had a very powerful bargaining tool in her pocket: A sponsor, Ban deodorant, that was willing to put forward the $55,000 needed to close the wage gap. The U.S. Open agreed, and the New York Times authored a headline, “Tennis Decides All Women are Created Equal, Too.”

It turns out, that headline might have been just a tad premature.

It took 34 years for all four tennis majors to offer equal prize money — the Australian Open finally made the switch for good in 2001, and the French Open and Wimbledon followed suit in 2006 and 2007, respectively, thanks in no small part to the advocacy of Venus Williams. But even that wasn’t the end of the fight.

Today in tennis, women still face sexism on a daily basis. That was particularly on display this clay-court season, where the two big Roland Garros lead-up events in Madrid and Rome were rife with disrespect for women. The trend continued at the French Open, where women were regularly treated like a warm-up act for the men. And a look at the prize money pools outside of the four majors show that while women’s sports are seeing significant growth globally, the wage gap in tennis is actually widening.

We’re going to get into all of that in today’s newsletter.

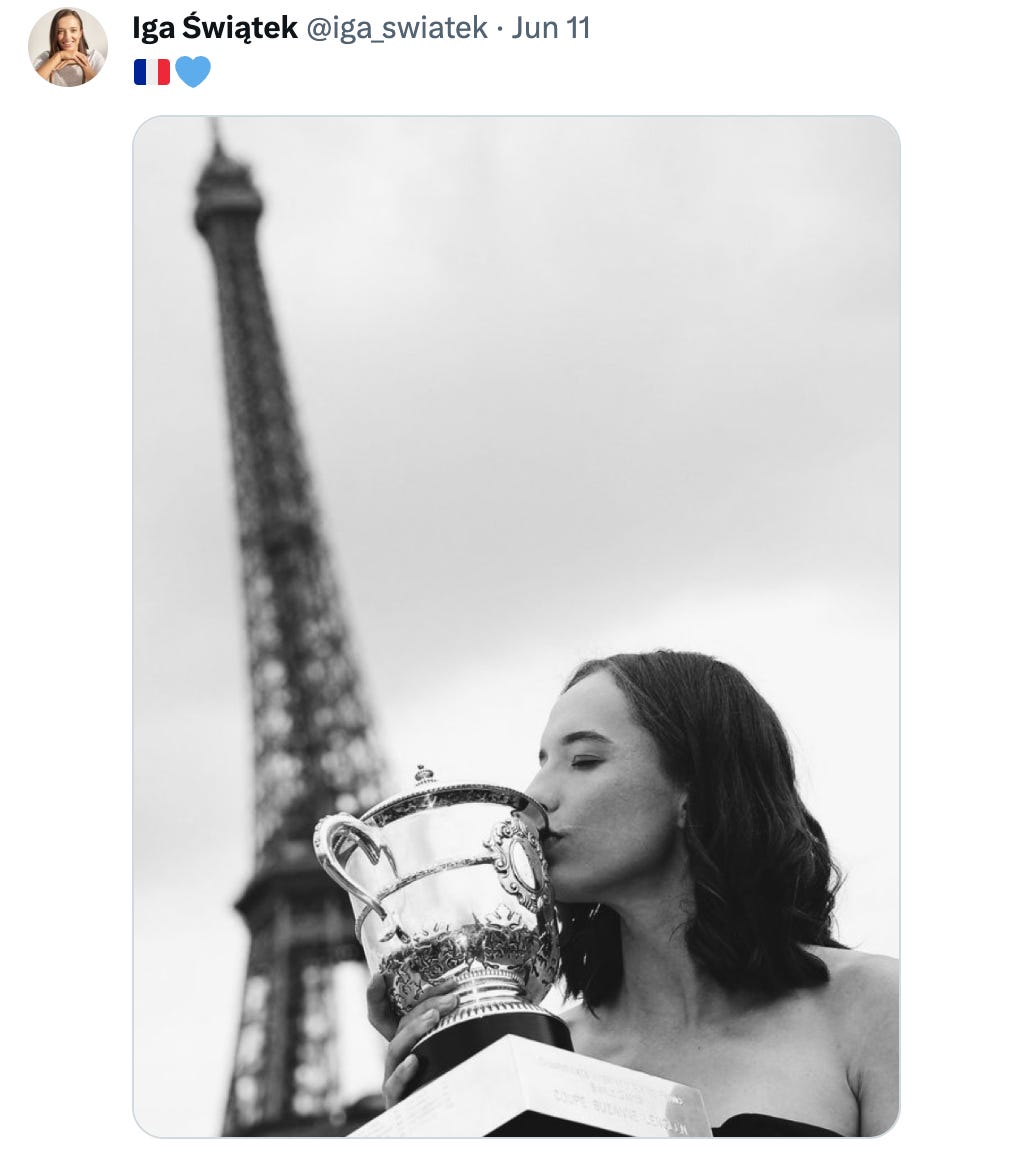

But first, I want to take a quick detour and say CONGRATULATIONS to Iga Swiatek for winning her third Roland Garros title, her fourth major overall. If you don’t know much about Swiatek, I suggest you start here. She’s so good. But it was fun to see her truly get tested this tournament thanks to a phenomenal performance by Karolina Muchova in the final. It’s a cliche, I know, but I truly wished they both could have won. In fact, I think all four semifinalists — Swiatek, Beatriz Haddad Maia, Muchova, and Aryna Sabalenka — should take a bow. After a fortnight of disrespect, these women dug deep and gave us dazzling performances when the lights shone the brightest. What a treat.

Also? I can’t get over this photo shoot:

Okay, fun detour over. Now it’s time to get down to business.

The French Open is committed to keeping women’s tennis on the undercard

Two Sundays ago, while I was running errands, I checked the Roland Garros app for a score update and immediately became nauseous: Aryna Sabalenka was up 5-0 over Sloane Stephens in just 20 minutes.

My queasy feeling had nothing to do with my feelings for Stephens or Sabalenka; I enjoy watching both of them play immensely. Rather, it was because of the timing and location of their match: nighttime on Philippe Chatrier Court.

A few years ago, Roland Garros joined the Australian Open and U.S. Open and began holding night sessions on its biggest show court. (Majors enjoy doing this because they can ticket night matches separately, and therefore make more money.)

But unlike the Australian Open and U.S. Open, which begin their night sessions around 7:00 p.m. and host one men’s match and one women’s match in each session, the French Open starts about 8:30 p.m. and only includes one match. Nine times out of 10, it’s a men’s match. Literally. Between the 10 night matches last year and the 10 this year, only two were women’s matches, one each year. This is incredibly disappointing because the night match on Chatrier is billed as the “match of the day.”

“The lack of women's matches in the night sessions at this year's French Open is disappointing,” WTA No. 5 Jessica Pegula wrote last week in a column for the BBC.

Pegula, who is on the WTA players’ council, said that the scheduling issue has been regularly raised with French Open organizers over the past year, and yet there’s no progress.

“We know people like women's tennis, and the fans like to watch it, but it feels like our product is undervalued here and in Europe in general.”

The primary excuse provided for this scheduling inequality is that men play best-of-five sets in Slams, while women play best-of-three. (If you want to know more about why that is, I’ve got you covered; spoiler alert: it’s because of the patriarchy!) Therefore, women’s matches are likely to be shorter than men’s matches, so to give the ticket buyers more entertainment for their dollar, the men must play.

But there are ways around this, from starting the night session earlier so you can have a men’s and women’s singles match on the schedule, to adding a doubles or legends match to the nigh session when women are playing, to just trusting in women’s tennis and showcasing it as the marquee product it is. And that excuse holds even less water when you realize that this isn’t the only disrespectful scheduling decision women have to deal with at Roland Garros.

For the last two years, women have started the day session on Chatrier Court nine out of 10 days. This is a problem because Parisian crowds are notorious for not arriving until mid afternoon, making the later matches in the day session much better for crowds and for television exposure.

I’m not an expert on math, but I do not believe that is equality.

My frustration around this situation is exacerbated because Amelie Mauresmo, former No. 1 and major champion, is the tournament director at Roland Garros. One would think she would prioritize women’s tennis. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. When asked about the scheduling discrepancy at last year’s tournament, Mauresmo told reporters that it was hard to find women’s matches to feature because the women’s game currently has less “appeal” than the men’s game. (She later offered a very, very lackluster apology for these comments, and said to judge her on what happened in 2023. Which, it turns out, did not help her case.)

(For more on Mauresmo’s handling of the scheduling, the best overall commentary and reporting on this comes via The Tennis Podcast, which is one of my favorite daily listens during tennis majors. The three hosts — David Law, Catherine Whitaker, and Matt Roberts — never let this topic get overlooked, and were dogged in trying to get Mauresmo to answer for it. You can listen to the section starting at about 45:00 in this podcast.)

It’s just so unfair that this is still happening, and that my fond memories of this year’s tournament will forever come with an asterisk.

Because I’ll never forget the pit in my stomach when I saw that 5-0 scoreline. Despite the fact that I know that length of match is not synonymous with quality of match, and I know that the burden should not be placed on any two individual women to *prove,* in one match, that women’s tennis deserves the spotlight, I found myself scared that if the match was well under an hour we’d never see a women’s tennis match get a showcase spot at the French Open ever again. It wasn’t fair. Thankfully Stephens came back to push the first set to a tiebreaker, and though Sabalenka won in straight sets, 7-6(5), 6-4, the match took an hour and 41 minutes to complete, putting it at the length of many three-set men’s matches. But the fact that so much pressure was on this one match is shameful.

I’ll also never forget Sabalenka’s post-match interview, when she effusively praised the crowd for showing up for the women’s-only night session, and said she “didn’t expect” there to be so many people in the stands.

Women’s tennis players deserve so much more than they’ve been conditioned to expect.

A ‘fiasco’ for women’s tennis in Madrid and Rome

Of course, there’s a reason why women in tennis today are used to unequal treatment — because it happens on a week in, week out basis. Nowhere was that more clear than during this clay-court season, at the Madrid Open in Spain and the Italian Open in Rome, Italy.

(Madrid and Rome are both co-ed clay-court events that act as warm-up events for the French Open. They’re just one level below the four majors on the prestige scale, and all the top players compete in them if healthy.)

Let’s start in Madrid.

Madrid offers equal pay, so in theory, women should be on equal footing with the men. But it certainly didn’t feel that way — or look that way, for that matter. The tournament is no stranger to accusations of sexism. You see, for a long time, Madrid had female models serve as ball girls for their matches. That went away in 2018 when the tournament changed ownership and was bought by IMG.

But this year, the fashion-models-as-ball-kids trend rose from the dead. There were two different crews of “ball kids” working the tournament: your standard crew, a mixed-gender group of young people dressed in conservative athletic clothing; and a crew of slim, young adult women dressed in short skirts and crop tops.

On TikTok, Eliza (@itslizasworld) did a phenomenal job explaining the situation.

Organizers responded to criticism by pairing the models’ crop tops with long, baggy gym shorts for the men’s final. It was truly a ridiculous sight.

Unfortunately, this was just one piece of the inequality puzzle.

During the tournament, two high-profile players celebrated birthdays: Carlos Alcaraz, the No. 2 ranked ATP player, and Aryna Sabalenka, the No. 2 ranked WTA player. The tournament marked both occasions. But not all cakes are created equally. Other WTA players, including former No. 1 Victoria Azarenka, definitely took note.

It turns out, Madrid saved the worst for last. After the women’s doubles final, which saw Azarenka and Beatriz Hadid Maia defeat Coco Gauff and Jessica Pegula 6-4, 6-1, none of the women were given a chance to make speeches during the post-match ceremony on court, completely going against a tradition in the sport that is present across all levels.

Apparently, the silencing was targeted at Azarenka, who publicly called out the tournament’s treatment of women in the tweet above, and, who the Guardian reports was complaining behind the scenes about scheduling. But literally taking the mic away from powerful and successful women is never the way to shut them up.

“I don’t know what century everyone was living in when they made that decision,” Pegula said. “Or how they had a conversation and decided, ‘Wow, this is a great decision and there’s going to be no-backlash against this.’

“I’ve never heard in my life we wouldn’t be able to speak. It was really disappointing. In a $10,000 [lower level] final you would speak It spoke for itself. We were upset when it happened and told during the trophy ceremony we weren’t able to speak. It kind of proved a point.”

After Madrid, the men’s and women’s tennis tours moved on to Rome, where things were off from the start because the Italian Open has one of the biggest wage discrepancies in tennis — the men make about $8.5 million in prize money, while the women only have about $3.9 million. (More on that in the next section, don’t worry.)

But again, it was a scheduling fiasco that showed the tournament’s true colors: The women’s singles final between Elena Rybakina and Anhelina Kalinina was moved to 11:00 p.m. on a Saturday night, after rain-delayed men’s semifinals, instead of being moved to Sunday afternoon either before or after the men’s final. There was barely anyone in the stands to watch one of the 10 biggest WTA Finals of the season.

Pam Shriver summed it up best when she said, “Madrid and Rome have been fiascos for women’s tennis.”

The myth of pay equality in tennis

Small cakes and sexualized ball girls and scheduling slights and silencing strategies deserve intense scrutiny. They send a message about priorities, and greatly impact how much exposure the sport gets, both on television and in person. These aren’t trivial matters.

But on the 50-year anniversary of King securing equal prize money at the U.S. Open, I think it’s crucial to take a close look at the state of pay equality in the sport.

And friends? The numbers, they are depressing.1

We know the majors have equal prize money, as do a few other joint events, such as the Indian Wells, Miami, and Madrid. But three other joint events — the Italian Open, the Canadian Open, and the Cincinnati Masters, do not.

Here are some important bullet points:

As I noted above, this year Italian Open paid the men more than twice the prize money as the women, at a ratio of $8.5 million to $3.9 million. Canada and Cincinnati both take place in the summer, so we don’t know the prize money pools yet, but last year, Canada paid the men $6.57 million and the women $2.7 million, while Cincinnati paid the men $6.97 million and the women $2.53 million.

Those are, obviously, massive wage gaps. And they’re getting worse. In 2010, all three tournaments (Rome, Canada, and Cincinnati) had a wage gap of about $430,000, with the tournaments paying the men $2.43 million and the women $2 million. Obviously, that’s not equal, but it’s so much closer than where we are now. In the past 13 years, prize money for the women at these tournaments has gone up between 25-75%, while prize money for the men has gone up 270-350%.

Overall, the total prize money pool for the ATP Tour outside of Grand Slam tournaments is about 250% of the total prize money pool on the WTA Tour, with the WTA offering about $60 million in prize money outside of major tournaments in 2022, compared to about $150 million on the ATP.

It’s been a strange stretch for tennis, with many tournaments canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic — including every tournament in China for three straight years — and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But both tours have been impacted, so I believe the numbers are still worth comparing.

While the focus is on the pay at the big events, I think the payouts at the smaller events are perhaps even more telling. At the 250 tournaments, which are the smallest held by both Tours, the ATP has a minimum prize money pool of $642,735 compared to $259,303 for the WTA. (Individual tournaments can pay above the minimums if they choose to.) At the mid-level 500 tournaments, ATP prize money is $2.014 million, compared to $708,637 on the WTA. And, at the 1000 level, which is what we’ve focused on the most in this section, ATP prize money is around $6.3 million, compared to $2.8 for the WTA.

So far this year, 10 players on the WTA Tour have earned more than $1 million, compared to 21 ATP players. The No. 100 player on the ATP money list, Max Purcell, has earned $349,699 in 2023, while Magdalena Frech, No. 100 in the WTA money list, has only earned $175,504.

EDITED TO ADD 6/17: Simon Briggs, a journalist at The Telegraph, alerted me to significant reporting he did last month which unveiled that the WTA actually pays about $32 million a year to subsidize prize money at tournaments. The money mostly goes to Indian Wells, Miami, Madrid, and Beijing to ensure that these four tournaments officially offer equal prize money. The owners of these events only pay 38% of the prize money, and the WTA makes up the other 62 percent. Briggs said that the ATP makes no equivalent contribution to their prize money pools. This obviously makes the prize-money situation even worse, and brings up many questions about how the WTA managed to agree to such terms and what the way forward it. I’ll keep you posted if I find out more.

I want to be clear about one thing: The WTA is not blameless in any of this, as the New York Times points out:

The WTA has committed some unforced errors. At the most important mixed tournaments, attendance is mandatory for women and men. The WTA requires participation at tournaments only in Indian Wells, Calif.; Miami Gardens, Fla.; Madrid; and Beijing, but not in Rome, Canada or Ohio, even though those events rank just behind the Grand Slam events in importance. Also, the WTA awards slightly fewer ranking points than the men’s tour does in Rome, Canada and Ohio, where the women’s champion receives 900 points compared with 1,000 for the men.

These minor differences have given tournament officials an excuse for paying women so much less, even though nearly all of the top women play the big optional events, unless they are injured.

But even if the WTA Tour made Rome, Canada, and Cincinnati mandatory and bumped the points up by 10 percent, there’s no proof that the tournament directors would do the right thing and pay the women equally unless it was contractually mandated. (After all, it’s not like the wage gap is just 10 percent — it’s closer to 300 percent.)

The truth is, the WTA has a hard time contractually mandating bigger prize money pools because despite trailblazers like King giving it such a leg up, women’s tennis still faces the sexist systemic barriers that the rest of women’s sports do on a day-in, day-out basis. As a result, it receives far less money for sponsorship and broadcast rights than its male counterparts. When it receives poor scheduling and exposure at the biggest co-ed tournaments, it simply makes breaking out of the cycle of secondhand treatment that much more difficult.

Over the next few weeks, we’re going to be taking a very deep dive into the current state of women’s sports, which I believe are at a crucial inflection point and MUST proceed with caution. Tennis is a great place to start that conversation — it is a prime example of the potential that all women’s sports have, and how long and bumpy the road to equality truly is.

TRANSPARENCY: These calculations are approximate. Wikipedia was my source, I did not go individually to each tournament’s website. And I had to do some Euro-to-dollar conversions for many of the European tournaments. For academic use of any kind, these numbers need to be checked. (I used 1.1 as the Euro-to-dollar conversion rate no matter the month or year).

Pssssssssssssssssst "If you want to know more about why that is, I’ve got you covered; spoiler alert: it’s because of the patriarchy!"