#FromOurArchives: Wyomia Tyus on protests, inclusion, and the ‘68 Olympics

"At the time, they were not about to bathe a Black woman in glory."

Hi, friends! Happy Black History Month.

Usually, after eight months, every Power Plays newsletter, even those that are initially free to all, go behind a paywall and become available only to paid subscribers. But over the next week, I’m going to re-publish a few of those old newsletters that share the stories of some of the Black women that made women’s sports the juggernaut they are today. Then, we’ll cap off the month with a brand new #FromtheArchives dive on a Black trailblazer.

Today, I’m sharing an adapted version of a newsletter I published four years ago about Wyomia Tyus, one of the greatest sprinters in U.S. history. Tyus won the gold medal in the 100m in the 1964 and 1968 Olympics, becoming the first man or woman to win back-to-back Olympic titles in the race. (She also two Olympic medals in the 4x100m relay — a silver in ‘64 and a gold in ‘68.) But because she was a Black woman in the 1960s, she didn’t get nearly the notoriety or fame or financial support she deserved, especially since any attention given to Black athletes after the 1968 Olympics went to John Carlos and Tommie Smith, who gave the Black Power salute on the 200m podium during the national anthem.

This newsletter features a pretty depressing 1970 article on Tyus’s overlooked legacy, as well as excerpts from her incredible autobiography, “Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story.”

#FromtheArchives: ‘Wyomia: Forgotten queen of the Olympics’

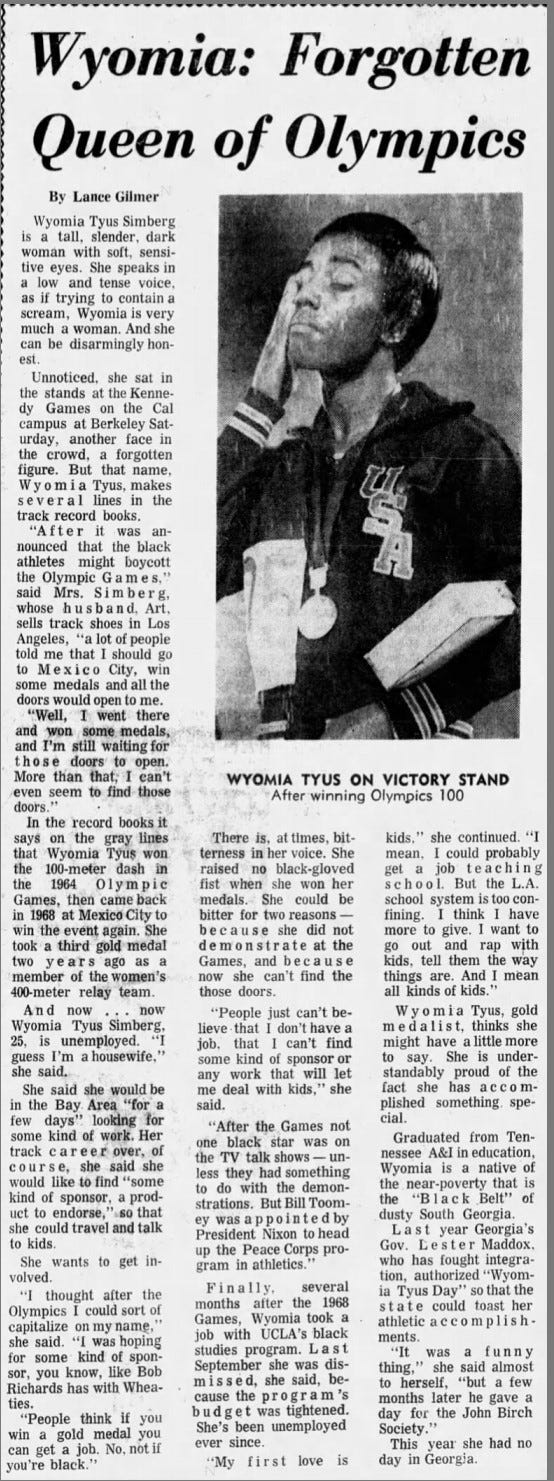

This article from the San Francisco Examiner on June 2, 1970, just two years after her Mexico City triumph, paints a bleak picture of what life was like for Tyus after she made history.

She wasn’t bathing in endorsement deals or celebrity; instead, she was an unemployed housewife, and not by choice.

“People think if you win a gold medal you can get a job,” Tyus says. “Not if you’re Black.”

A few things to note:

WHAT IS THIS LEDE??? “Wyomia Tyus is a tall, slender, dark woman with soft, sensitive eyes. She speaks in a low and tense voice, as if trying to contain a scream, Wyomia is very much a woman. And she can be disarmingly honest.” I … cannot.

In her book, Tyus makes it known that she is *not* crying in that photo from the medal stand; it was merely raining.

Claiming she is “bitter” because she didn’t demonstrate at the Olympics in ‘68 is ridiculous, because, first of all, she did demonstrate — she wore black shorts instead of white shorts to show solidarity with John Carlos and Tommie Smith after their podium protest, and dedicated her relay medal to them. Plus, as she details in her book (and as we will touch on below), she wasn’t frustrated that she “didn’t” raise a fist on the podium; she was frustrated because women were left out of the movement altogether.

Excerpts from ‘Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story’

I really do love everything about Tigerbelle, but my favorite section is when Tyus is reflecting on what happened before, during, and after the Mexico City. Olympics. It’s a perspective that is missing from almost every remembrance of the momentous competition.

Her college track coach, the famous Ed Temple, was among the many who thought that Smith and Carlos doing the Black Power Salute on the podium after the 200m race was the reason why her 100m title defense didn’t get much attention. But Tyus astutely notes that her 100m race happened before Smith and Carlos raised their fists; the primary reason why she was not given the proper attention and respect was because she is a Black woman.

Since the very beginning here at Power Plays, we’ve discussed sports as a beacon of power and oppression for white, cisgender men, and how women’s sports — and everything that comes with it — is often treated as less of an opportunity, and more of a threat.

Tyus, of course, says that better than I ever could. But I do think that sport is at its best when the powerless use it as a means to seize power; we’re seeing marginalized communities do that more and more as the years go on, and it’s why it’s crucial to continue to fight for a sports world that is inclusive, so that power can be accessible to all.

Tyus also uses the book to take us behind the scenes before Mexico City, and notes that as they were planning their protest against racism in the United States and human rights abuses across the globe, Smith and Carlos and their cohort never reached out to female athletes to join them. There was no communication, even though it would have been very easy for them to reach out — Tyus’s boyfriend at the time was involved with the movement.

“We should have been included in the organizing, should have bene consulted. It would have made a difference,” Tyus says.

I love that in telling her story, she manages both to acknowledge the power and impact that Carlos and Smith’s protest had, but is also very frank about how it felt to be less than an afterthought. Both are valid. Both are the story. Both matter.

She also uses this experience to provide great guidance to anyone who is trying to build movements going forward: Inclusivity is the way forward: “[W]hen you are trying to build a movement, if there are a lot of people who get left behind or are not spoken to, that’s a weakness.”

Given what’s going on in the women’s sports world right now, her words resonated with me on multiple fronts.

If you’re fighting your own community’s marginalization by further marginalizing others, you’re wasting energy instead of gaining steam. No matter how small your platform is at the start, you can build it up much higher if you build it out on the ground first.

Thanks for reading Power Plays. Happy Friday. Happy Black History Month. Have a good weekend.

And, sincerely, thank you.

Aaaarrrrrrggghhhhh, so frustrating to hear how Carlos and Smith didn’t even bother to include their fellow female athletes in the protest. And the fact that this blind spot is still so prevalent today! Gah.