Racism's central role in WNBA coverage

An important study on WNBA media, plus some softball history.

Hi friends, welcome to Power Plays, a no-bullshit newsletter about sexism, etc., in sports, written by me, Lindsay Gibbs.

Later this week, we’re kicking off an expanded version of our #CoveringTheCoverage campaign by taking an in-depth look at the people and places that are having success covering women’s sports. I’m extremely excited to share that work with you all.

But first, to get us in a #CoveringTheCoverage mindset, we’re looking at a very important study that quantifies something we’ve long known is true: White WNBA players receive far more coverage than their Black counterparts, even though the league is predominantly Black.

Also, we take a look back through the Power Plays archives to remember the first pro women’s softball league in the United States, in honor of the Women’s College World Series.

Remember to subscribe and support Power Plays if you can.

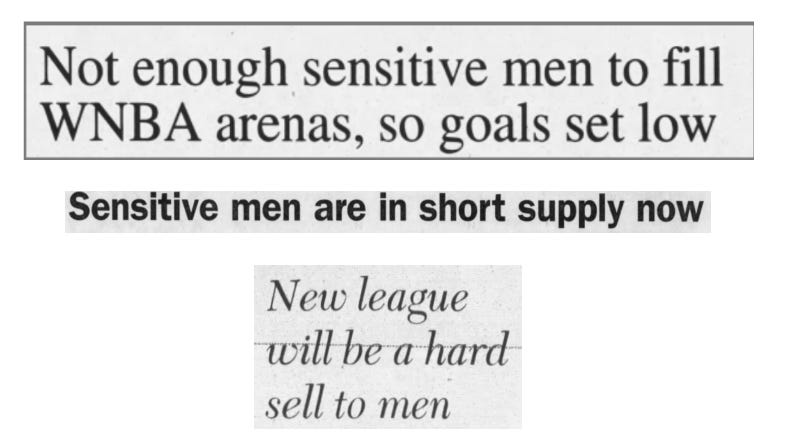

ICYMI: Recently, paid subscribers got my deep dive into “Women's basketball and the 'female identity',” which is about Sonja Hogg and the Lady Techsters and the weaponization of femininity. The newsletter includes a few clips from the archives that still have readers screaming all these many days later.

Here’s a teaser:

The text reads:

In the interest of equal rights for men, and with a touch of vestigal voyeurism, I attended the Women’s Basketball Classic at Madison Square Garden over the holidays. I had never before been in a women’s locker room.

Subscribe now, there’s more where that came from, including a pretty epic cameo from current Indiana Fever coach Marianne Stanley.

If that’s not enough to convince you, last month Power Plays paid subscribers also got a deep dive into coverage of the WNBA when it first launched. Here’s a taste of that post:

See how much you’re missing out on?

Anyways, now that I’ve scarred you, let’s do this, friends.

Report: White WNBA players received twice as much coverage as Black players in 2020 season

Last summer, Risa F. Isard, a research fellow with the Laboratory of Inclusion and Diversity in Sport at the University of Massachusetts, was scrolling through Twitter when a thread by WNBA fan Michael McManus (@getdisdance) caught her eye.

The thread was about the media’s centering of 2020 No. 1 overall draft pick Sabrina Ionescu (SI) and other white WNBA players, and how discordant that was given the predominantly-Black league was dedicating its 2020 season to the #SayHerName campaign, lifting up the often-overlooked stories of Black women who are victims of police brutality.

“If women’s basketball is only marketable with a white face you may have to ask yourself what role do you play in making that true,” McManus tweeted. “If we are going to call out systemic racism and white supremacy, we have to do it in all facets of society.”

The thread struck a nerve with Isard, who is pursuing a Ph.D. in the McCormack Department of Sport Management.

“I kept thinking about it all last summer,” she told Power Plays. “I couldn’t unsee it.”

Isard wanted to know if the coverage was really as skewed as it seemed, so she teamed with Dr. E. Nicole Melton, an associate department chair and associate professor in her program, to research the issue.

What they found was staggering.

“We went into this research thinking we were going to find racism, but we didn’t think we’d find it to this magnitude,” Isard said.

Isard provided Power Plays with a list of the top 10 most-mentioned players from last summer. Four of the top five players are white, as are five of the top 10. The WNBA as a whole is over 80% Black.

Sabrina Ionescu

Breanna Stewart

Sue Bird

A’ja Wilson

Diana Taurasi

Satou Sabally

Angel McCoughtry

Chennedy Carter

Candace Parker

Courtney Vandersloot

Isard and Melton focused their study on the 2020 season, since that was supposed to be the summer of anti-racism. They monitored the digital WNBA coverage on ESPN, CBS Sports, and Sports Illustrated, downloading more than 550 articles tagged as WNBA content. Software helped them sort the data, but they also had to go in and manually count mentions when players had common last names — such as Jordin Canada and Jackie Young. In their database, they controlled for quantifiable performance statistics, like points and rebounds, and also used established academic methods to code for race and gender expression and publicly-known sexuality.

In every single case, they found that media coverage heavily favored white players.

Here are the biggest takeaways from the study, as first reported last month in an article for Sports Business Journal:

A’ja Wilson received *half* as much coverage as Sabrina Ionescu. Wilson, who is Black, was the 2020 MVP and made the WNBA Finals with the Las Vegas Aces. Ionescu, who is white, was the first overall draft pick in 2020 and played in only three games with the New York Liberty before getting injured and leaving the Wubble.

White players got more than twice the mentions as Black players. In the 550 articles, Black players were mentioned an average of 52 times, compared to 118 times for white players.

Black players dominated awards, but white players dominated conversation. Black players won 80% of the postseason awards (MVP, Rookie of the Year, Defensive Player of the Year, Most Improved Player of the Year, and Sixth Woman of the Year.) But the top three most talked about players in the league were white.

The commissioner got more attention than Black players. Only one Black WNBA player, A’ja Wilson, got more media mentions than WNBA commissioner Cathy Engelbert, who is white. Don’t get me wrong, Engelbert’s first year at the helm was certainly noteworthy, but she wasn’t out there on the court on a day in, day out basis!

Gender presentation mattered much more for Black athletes. White athletes who presented more masculine received more than five times the amount of mentions (212) as Black players who presented as more masculine (41).

WNBA press releases only showed bias towards top performers. Isard and Melton also analyzed official WNBA and team press released, and discovered that those press releases did not show racial bias; rather, they only showed a preference towards players who scored more points, which is a very understandable preference! So, the media’s bias isn’t inevitable; it’s a deliberate choice.

None of the results surprised McManus, who has been beating the drum about the racially biased coverage for a long time.

“It’s hard for me to completely describe the feeling, but I think that a lot of times as a Black person I notice the most simple and subtle forms of bias — where someone is placed on a graphic, how announcers describe players, the way we frame the accomplishments and or ability of players,” McManus told Power Plays.

He is hopeful that the research by Isard and Melton will help drive the conversation forward, and help media members become more aware of their own biases.

“I think sometimes people think that racism is one action, one egregious comment, but it’s a lot more nuanced and plays a role in every thing. No matter how much we say we want to support Black athletes, the study showed that we aren’t trying as hard as we say,” he said.

“I usually have to play the villain role in these conversations because no one wants to actually hear that they are contributing to a problem, but I think that Risa’s research showed that if we have those conversations and really think critically about our work we can be more equitable.”

You all know that here at Power Plays, we’re huge of breaking coverage metrics down like this, because everyone in media needs to be conscious of the choices that they make and the impact that those choices have. Reporters are not PR people and not in charge of promoting athletes, but that doesn’t mean our coverage choices happen in a vacuum.

“Media begets more media, which leads to more sponsors and more endorsements, which leads to white players getting bigger payouts,” Isard said.

And I wish it went without saying, but it doesn’t — media coverage of Black players needs to not only exist, but respect Black players enough to spell and pronounce their names correctly! Britni de la Cretaz recently wrote about the mispronunciation problem in Vice, and Khristina Williams of Girls Talk Sports and WNBPA president Nneka Ogwumike called out the disrespect on Instagram.

This is not a WNBA-specific problem. In 2017 for ThinkProgress, I wrote about two studies by Dr. Cynthia Frisby, that found that coverage of athletes in women’s sports got became even more racist and sexist between the 2012 and 2016 Olympics, and that “female athletes of color were more likely than white female athletes to receive microaggressions related to objectification, second-class citizenship (inferiority), restrictive gender roles, and commentary that relates to their body shape and body image.” Frisby also studied coverage of Serena Williams between 2011 and 2016, and found “mediated messages in news centered around Serena’s body, her blackness, and clothing.”

Frisby noted in her study that Serena was often described as “pummeling,” “overwhelming,” and “overpowering” her competition. She also found that, while violent metaphors aren’t unusual in sports media, “descriptions of Serena’s power and the strength behind her victories have taken this type of hyperbole to another level — one that suggests she’s absolutely unparalleled in her strength and capacity for violence, especially as compared with her white opponents.”

Of course, all of this is happening within a media sphere that is already giving women in sports far less ink than they deserve. For decades, Cheryl Cooky, a professor of interdisciplinary studies at Purdue University who studies the representation of women’s sports in the media, has been teaming with Michael Messner, a professor of sociology and gender studies at USC, to research the coverage of women’s sport and to track the quantity and quality of coverage of women’s and men’s sports. (They are the #CoveringtheCoverage pioneers, it must be said.)

Cooky and Messner’s latest report, “One and Done: The Long Eclipse of Women’s Televised Sports, 1989–2019,” discovered that “in 2019, coverage of women athletes on televised news and highlight shows, including ESPN’s SportsCenter, totaled only 5.4% of all airtime, a negligible change from the 5% observed in 1989 and 5.1% in 1993.”

With such a small slice of the pie, those covering women’s sports shouldn’t focus on giving less coverage to the white athletes of the WNBA, but rather at giving more coverage to everyone in the sport, and making sure that the growth centers Black players, respects their names, and avoids racial microaggressions.

“Women’s sports aren’t getting enough coverage, period, and so let’s fix that, and when we do, make sure that Black athletes getting fair share too,” Isard said.

Or, as McManus put it: “The ultimate goal is to grow the game, but I don’t think it should be at the expense of Black women who have laid the foundation.”

PS: Are you subscribed to The Black Sportswoman yet? If not, please fix immediately.

#FromtheArchives: When Billie Jean King founded a pro softball league

So, this is my confession time: I had planned on using this space to write about Naomi Osaka and mental health, my empathy and admiration for Osaka, my hatred for a lot of the takes we’ve seen lately on both sides (I am NOT in favor of banning press conferences forever or removing all media requirements from pro athletics, nor should we publicly ridicule and threaten to default athletes for prioritizing their mental health), and also open up about my mental health struggles over the past few months, what I’ve learned, what’s next for me and Power Plays (don’t worry — things are revving up, not going away, I’m just going to be reaching out for actual help instead of actively hating myself and hiding out from the world because I’m unable to do everything myself), and why I think it’s imperative that the conversation around mental health moves to one of a middle ground, between recovery and rock bottom, where most of us live full time.

BUT as you can see my thoughts are still pretty jumbled, and I haven’t been able to pull something coherent out of my ramblings yet, so I’m giving you the cliff notes and pressing pause on that newsletter for now.

Instead, considering I have been watching so much softball — and I hope you all have, too, since the Women’s College World Series has been phenomenal — I thought we’d revisit a very old Power Plays newsletter, which took us back to 1976 when Billie Jean King founded a pro softball league.

Here’s an article from The Hartford Courant on April 7, 1976, announcing the launch of the International Women’s Professional Softball league.

(While these are two screenshots, read as one, reading the entire left column before moving to the right.)

Remember last month, when we looked at the coverage of the WNBA when it first launched? How so much of it was stressing, in the most patronizing way possible, that women’s basketball should be taken seriously?

Turns out, that wasn’t a new playbook!

As Sandra McKee wrote in this article from The Evening Sun on August 24, 1976, “If baseball fans came to see little girls play a game filled with mental and physical errors, the fans were disappointed. the women were professional, well muscled, and coordinated.”

I’m running out of room in this newsletter, so I’m not going to post the rest of the archival clips, but I do encourage you to go and revisit the rest of the newsletter — the archives track the rise and the fall of this league, and honestly, if you’ve followed the rise and fall of any women’s sports league in history, it will all sound very familiar!

Can you imagine a world where that league would have been given the proper time and investment to flourish? *Chokes back tears*

Anyways, I hope you will all tune in this week for the WCWS championship series, a best-of-three series between Oklahoma and Florida State, which starts on ESPN tonight (Tuesday, June 8) at 7:30 p.m. ET.

Thanks for supporting Power Plays, friends!