The controversies and corruption that have defined the World Cup lead-up

"Our most painstaking battle has been with our own federation."

So. The World Cup starts in just two days. That? Is ridiculous.

I’m so excited, but at the same time, I don’t feel ready in the slightest.

So, this newsletter is to help get us ready. Not for the on-field match-ups, necessarily. There are other places you can go for that. (Such as The Athletic, The Equalizer, The Guardian, etc.)

Rather, I want to give us the off-the-field context we need to truly understand and appreciate what we’re watching over the next month in New Zealand and Australia, as a record 32 teams face off in what should be the most-watched women’s sporting event in history.

Because, as we know, these women have had to fight so much more than just their opponents in order to make it to this stage. In most cases, they’ve had to directly battle against the very federations that are supposed to be supporting them — the very federations that, in fact, will profit off of their successes this summer.

First, we’re going to refresh ourselves on the basics of the tournament. Then, we’re going to look at what’s been going on behind the scenes in 10 countries that will be competing this summer.

Okay, friends. Let’s do this.

First things first, here are the 32 teams participating in the 2023 Women’s World Cup

Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Haiti, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Panama, the Philippines, Portugal, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, Vietnam, Zambia.

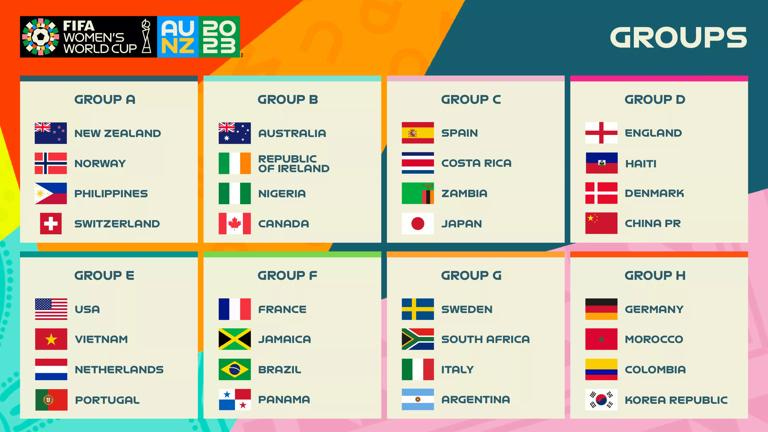

These 32 teams are separated into eight groups, which you can see here in a graphic that I borrowed from the FIFA website:

These groups will play in round-robin games, after which the top two will advance to the knock-out rounds in the Round of 16.

Here’s the TV schedule. The time zone difference is brutal and complicated so I recommend just downloading it into your online calendars so you don’t miss anything.

Now let’s talk about money

I’m going to cut to the chase: The women’s tournament still doesn’t have equal prize money with the men’s. I know, I know, you’re shocked.

Prize money has more than tripled since 2019, which is good. This year, there is $110 million in prize money up for grabs, which is a step in the right direction considering the pool was only $30 million in 2019 and $15 million in 2015.

Most notably, this year FIFA is finally giving direct payments to players, so it is not completely up to each individual federation whether its players get compensated.

Here’s how that works: For each round, FIFA has earmarked prize money to be given to players and prize money to be given to federations. The 16 nations that don’t advance past the group stage will get a total of $2.25 million — $1.56 million for the federation, and $690,000 to be shared among the 23 players on each team. That means that every player will leave the World Cup with at least $30,000. The prize money pool increases each round; the champions will receive $10.5 million — $4.29 million for the federation and $6.21 million to be distributed to players ($270,000 each). Of course, federations can (and should!) pay players additional bonus money, but at least we know some of the money is going to players.

You’ll see how important this step is when you read about the fights happening within federations later in this newsletter. The truth is, while $30,000 isn’t nearly enough, it will mark the most money that many of the women in the World Cup have ever received playing football.

A recent report from FIFPro exposed just how bleak the state of pro women’s soccer is across the world — only 40% of players that competed in confederation championships (which served as qualifiers for the World Cup) consider themselves professional athletes. A staggering 29% of players reported not receiving any payment from their national team, which is unconscionable given that 66% of players had to take leave from their primary jobs to participate in the qualifying tournaments – and that leave was unpaid for 29% of the players.

The truth is, FIFA can do more and should be doing more to help professionalize and stabilize women’s soccer globally.

I was proud to see the Australian national team use their platform as hosts and contenders to post a video this week putting pressure on FIFA to equalize prize money — right now, FIFA is only paying the women 25% of what it pays the men, despite having $4 billion in reserves.

Now, here’s an overview of some of the off-field issues players have been fighting in recent months, as they tried to prepare for the most important tournament of their lives:

The head coach of Zambia women’s football team has been accused of sexual misconduct.

According to The Guardian, Zambia head coach Bruce Mwape is currently under investigation by FIFA for allegations of sexual abuse, and players have been threatened into silence due to the team’s on-field success.

“If he [Mwape] wants to sleep with someone, you have to say yes,” an anonymous player told the Guardian. “It’s normal that the coach sleeps with the players in our team.”

Players have been left off of the Colombian team for speaking out against abuse and discrimination.

Brenda Elsey covered this in Global Sports Matters and Power Plays earlier this month. Here’s a quick refresher:

“Since 2015, active and former players, trainers, and their families have reported disturbing cases of sexual harassment, assault, and wage theft,” Elsey said. “In short, the men who run Colombian football have shown that their corruption and sexism overpower their desire to build a winning team.”

Players such as midfielder Yorelí Rincón have been left off of the World Cup roster for speaking out against gender inequities and lack of payment within the program. But exclusion from the national team is only a part of the story — women who speak out have been subjected to everything from “constant abuse from critiques of their physical fitness to rape threats.”

French players fought to oust their head coach to protect their mental health.

It’s also been a tumultuous few months for the French national team. In February, captain Wendie Renard publicly stated that she would not play the World Cup to protect her mental health because she “can no longer support the current system.” Two of her teammates, Marie-Antoinette Katoto and Kadidiatou Diani, followed her lead. Their problem was primarily with the toxic culture created by head coach Corinne Diacre.

The French Federation launched an investigation, and ultimately found that the situation was irreparable and fired Diacre. Hervé Renard was hired away from the helm of Saudi Arabia’s men’s national team and appointed as the head coach of Les Bleues less than four months ago, and Renard and company returned to the team.

That’s a happy ending, but far from an ideal World Cup prep.

Despite winning the Olympics in 2021, Team Canada went without pay and saw its federation take away resources.

After winning the Olympics in 2021, Canada should come into this World Cup on a high, but unfortunately, their preparation has been overshadowed by a dispute with their federation over, you guessed it, pay and training conditions.

Earlier this year, the Canadian players came forward and said they had not been paid for 2022 and were being forced to cut back on training camp days, the number of players in camp, and support staff due to budget concerns. They threatened to strike during the SheBelieves Cup in February, but called the strike off after Canada Soccer threatened to take legal action against them.

The players had hoped to secure a long-term bargaining agreement ahead of the tournament, but instead only have an interim funding agreement in place that lasts until the end of this year. They had zero home friendlies in the lead-up to this World Cup and were given far fewer resources to prepare for the women’s World Cup than Canadian men were to prepare for the men’s World Cup just months prior.

"The success of the national teams is inspiring the entire country and the future should be brighter than ever," Christine Sinclair said in March.

"However, as the popularity, interest and growth of the women's game has swept the globe, our most painstaking battle has been with our own federation."

The Haitian federation’s president was banned for life by FIFA for sexually abusing female players. That ban was then overturned.

Haiti qualified for its first World Cup by beating Chile 2-1 behind two goals from teenager Melchie Dumornay (known as Corventina), who is a bonafide star and recent signee of Olympique Lyonnais. This team is electric, and definitely one to keep an eye on during the group stage.

But behind the scenes, these women have faced many hurdles — and I’m not just talking about the natural disasters that have ravaged Haiti or the political upheaval in the country following the assassination of president Jovenel Moïse in 2021.

In 2020, Yves Jean-Bart, the then-president of the Haitian Football Federation was banned for life after an investigation by FIFA found him guilty of “sexually abusing female players as young as 14, keeping mistresses and preying upon girls from impoverished neighborhoods.” Some of his victims were allegedly members of the senior women’s national team. But earlier this year, the Court of Arbitration for Sports (CAS) overturned the lifetime ban, due to “inconsistencies and inaccuracies in statement of alleged victims.”

FIFA appealed that decision, but Swiss federal judges dismissed that appeal earlier this month. Jean-Bart has declared that he reclaimed his position as the president of Haitian football, and it remains to be seen if he will attend the World Cup.

Jamaica had to crowdfund its way Down Under. Seriously.

In June, multiple players from the Jamaican national team shared a statement on social media expressing disappointment with the lack of support from its federation.

“On multiple occasions, we have sat down with the federation to respectfully express concerns resulting from subpar planning, transportation, accommodations, training conditions, compensation, communication, nutrition and accessibility to proper resources,” the statement said.

“We have also showed up repeatedly without receiving contractually agreed upon compensation.”

Well, apparently their concerns were not properly addressed, because in the following weeks, two crowdfunding campaigns popped up for the team — one, “Reggae Girlz Rise Up,” was set up by the mother of midfielder Havana Solaun, Sandra Phillips-Brower; the other by the Reggae Girlz Foundation. Together, they’ve raised nearly $100,000.

“If I can somehow make this journey smoother for them — and let them focus on what they’d love to do is play soccer — they shouldn’t be worried about the politics or getting a flight or getting accommodation,” Phillips-Brower said. “They should be able to go there and do what we they qualified to do, just play soccer.”

The Reggae Girlz are currently in Australia after a 10-day training camp in the Netherlands, so the fundraising has been successful enough to get them to their final destination, but goodness gracious god almighty it should never have to come to this.

South Africa went on strike and refused to play one of its final warm-up games.

The AFCON champions did not have an ideal time in the lead-up to the Women’s World Cup — the team actually went on strike and refused to play in one of its final warm-up games against Botswana, and the federation had to recruit players as young as 13 (!!) to take their place.

According to the Associated Press, the strike was due to — what else — poor pay and a general lack of investment. Thankfully, the labor solidarity paid off, and a couple of days later the South African Football Association (SAFA) ended the dispute with Banyana Banyana thanks to a donation by the Motsepe Foundation reported by Inside World Football to be worth about $320,000.

The Lionesses are in a fight with the FA for more than the bare minimum.

Last summer, England won the Euros, bringing unprecedented attention and commercial opportunity to the Lionesses and establishing the team as one of the favorites for this summer’s World Cup.

But unfortunately, according to Suzanne Wrack at The Guardian, players are headed to Australia and New Zealand dealing with an ongoing dispute with the English Football Association over bonus payments. The FA refuses to pay the players any bonus money on top of the money that FIFA is earmarking specifically for players. The players believe they are entitled to additional bonuses — which teams such as the United States will receive from their federations due to collective bargaining agreements — and believe that the FA, which likes to pretend it champions equality, should want to do more than just the bare minimum to support the players. They are not willing to be quiet about this issue.

Adding to the frustration, players are also prevented by the federation from making physical appearances and social media posts for their personal sponsors in the lead-up to the World Cup, limiting their marketing value and earning potential.

“It is frustrating, but I think that’s the way the women’s game has predominantly been,” Lucy Bronze told the Guardian. “As a team we’ve always been pushing in the background, it’s only been recently that it’s been made more public and people are more aware of it, but it’s something we’ve always had to do as players.”

The Nigerian federation canceled an important camp before the World Cup, leaving the team ill prepared.

Trouble has been brewing between the Nigerian football federation and the Super Falcons for quite some time. In the African championships last year, the Super Falcons refused to train ahead of their match against Zambia due to unpaid bonuses.

In the lead-up to this World Cup, the Nigerian football federation has done some wild things, including cancelling a two-week camp in Nigeria and forcing head coach Randy Waldrum to choose between bringing his preferred goalkeeper or his most relied upon assistant coach to Australia.

“I know we’re not prepared the way we need to be,” Waldrum told John Krysinsky on the “Sounding Off on Soccer” podcast. “I have been very frustrated in recent months, in particular in recent weeks, with the federation and the lack of support we’ve gotten in so many different levels.”

Some top Spanish players are boycotting the World Cup due to concerns about the head coach.

Last September, 15 Spanish players sent an open letter to their FA saying that as long as Jorge Vilda remained as head coach, they would not play on the team due to concerns over his Vilda’s coaching and behavior, as well as unprofessional conditions in general. But the FA vigilantly stuck by Vilda, and the incredibly deep Spanish squad ended up having on-field success without those 15 players, going 8-1 in friendlies since last fall, including the team’s first win over the United States.

Ultimately, a few players who signed that letter — Aitana Bonmatí, Ona Batlle and Mariona Caldentey — ended up rejoining the team for the World Cup, in part because of improved travel accommodations and training resources provided by the federation. But the team is still missing some key players. Sam Marsden at ESPN has a good breakdown of the entire rift.

Here’s the thing: This 2,000-word list is only the tip of the iceberg. These are only the disputes that have been publicized and that I can recall. (I am confident that as soon as I send this into your inbox, I’ll remember disputes happening within other federations.)

I didn’t compile this all to depress you. Rather, I compiled it because I think that its crucial to watch the Women’s World Cup knowing that the phenomenal play you’re watching is, for the most part, happening despite the actions of the men in charge, not because of them.

For anyone else struggling with the timezones, this tool has been soooo helpful! https://2023wwc.alisongale.com/schedule?tz=computer